Base Rate Fallacy At Work in SEC v. Coinbase

Always finding a contract in investment contract cases means nothing

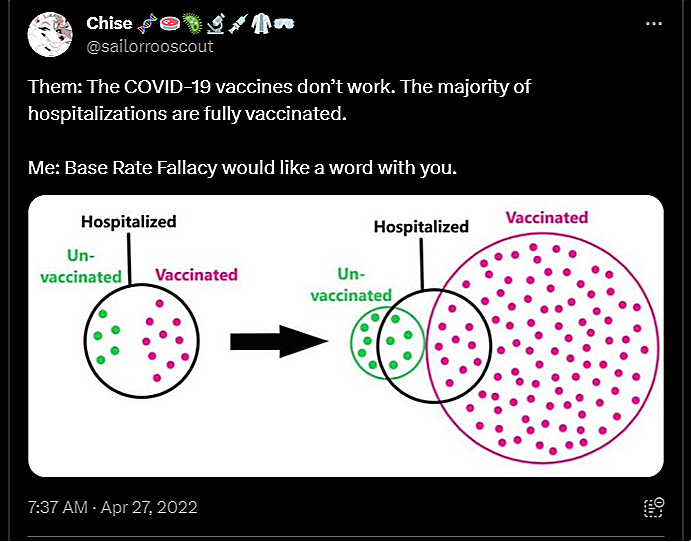

We are sure you heard a version of this argument: “The COVID-19 vaccines don’t work. The majority of hospitalizations are fully vaccinated.” Indeed, it sounds bad if, say, 50% of the hospitalized are vaccinated. That sounds like the vaccine is not working, doesn’t it?

Whether COVID-19 vaccines work or not is a complicated question. We don’t really have a position on that. One thing is clear, though. The majority of hospitalizations being fully vaccinated tells us absolutely nothing about vaccine effectiveness.

The reason is due to this concept called the base rate fallacy. Here is one of the best infographics we came across that powerfully illustrates it:

Why are we talking about COVID-19 vaccines in a legal insights blog, especially on the day of SEC v. Coinbase oral arguments? Let’s introduce another tweet from the chain above.

Indeed. The base rate fallacy can show up in lots of places, including crypto litigation.

Confused? So were the six of the most esteemed legal minds in the country who happened to have filed an amicus brief in SEC v. Coinbase (PDF). Among other things, they stated:

To date, every arrangement the Supreme Court has deemed an “investment contract” promised the investor some ongoing, contractual interest in the enterprise’s future endeavors.

And:

Likewise, every “investment contract” identified by the Second Circuit has involved a contract granting a surviving stake in an enterprise.

And:

Not surprisingly, no decision of the Supreme Court or the Second Circuit has ever found that a “scheme” that does not involve a contract could qualify as an “investment contract.”

The problem? This is just another base rate fallacy. The fallacy is beneficial for crypto, but bad for the SEC, investor protection, and the public at large.

This is what Those Nerdy Girls stated in regard to vaccination and COVID-19:

Rather than the % of the hospitalized who are vaccinated, we care most about rate of hospitalization in the vaccinated vs. the unvaccinated.

The same holds true for crypto, or, more broadly, for any non-cash-flow-generating asset. Rather than the % of the investment contract decisions that found a contract at the Supreme Court or the Second Circuit, we care most about the rate of investment contract findings in the absence of contracts vs. presence of contracts, or, alternatively, the rate of investment contract findings in non-cash-flow-generating assets vs. cash-flow-generating assets.

So, here is the same graphic, with labels (and colors) changed. Please note that we used a single red dot for visualization purposes, the same reasoning holds whether that number is one or zero.

So, what if every investment contract finding involved a contract? That, in and of itself, means nothing. A contract is almost always present with cash-flow-generating assets - it must be so because it should be clear how the cash will move between parties and under what conditions. A non-cash-flow-generating asset, on the other hand, often does not need a contract. Why would it? There is no cash involved, so there is no lingering question about how cash will be distributed.

Said differently, we can reproduce the above infographic by slightly changing the labels:

20th-century finance was about cash-flow-generating assets. That was the backdrop against which the securities laws were enacted. That’s what people bought and sold. Naturally, the disputes that reached the high courts were, for the most part, about cash-flow-generating assets. That one doesn’t find a contract in those cases is akin to saying that one didn’t find an NBA-level basketball player in the NFL. It may be true but it tells us nothing about whether or not NBA talent exists in the US.

The exact same is true with always finding a contract in investment contract disputes. It tells us nothing about whether or not a contract is a necessary condition for making the legal conclusion of an investment contract. Absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence.

The fallacy has already made the rounds to some extent. Rep. Ritchie Torres picked up on the argument, we talked about how he pressed Gensler on the phrase “investment contract” in one of our previous posts. Below, we are reproducing the pertinent part of the exchange:

REP. TORRES: In August, there were six law professors from law schools as preeminent as Yale, who came to the following conclusion – “No decision of the Supreme Court has ever found that a scheme that does not involve a contract could qualify as an investment contract.” And so, do you disagree with that statement? And if so, could you please cite the decision of the Supreme Court that has found an investment contract in the absence of an actual contract?

MR. GENSLER: The SEC has been in front of multiple courts and the investment contract has been…

REP. TORRES: What’s the name of the case Mr. Gensler? The Supreme Court case that has found an investment contract in the absence of an actual contract, you’ll need to cite a case…

MR. GENSLER: The SEC over the decades, whether it’s…

REP. TORRES: Can you cite a case?

MR. GENSLER: Whether it’s whiskey caskets, whether it’s crypto, if the public is investing based upon the efforts of others…

REP. TORRES: I find it telling that you cannot cite a single case.

MR. GENSLER: That’s a security.

REP. TORRES: How about a Second Circuit case? Can you cite a single Second Circuit case that found an investment contract in the absence of a contract?

MR. GENSLER: I understand where you’re trying to go. And I’m gonna leave that to the very fine attorneys at the SEC in front of the courts, but I’m saying the core principles that…

REP. TORRES: Mr. Gensler, let me finish. This is, this is a question to which you should know the answer, because the definition of an investment contract is the central issue. That’s what determines the extent of your authority. That’s what determines the applicability of federal securities law to crypto transactions, and your inability to answer that question is baffling to me.

MR. GENSLER: I’m answering it consistent with what the Supreme Court has said which is the law of the land which is a four-part test.

REP. TORRES: And yet you cannot cite a single case that can support your argument.

MR. GENSLER: It’s called Howey, it’s called Reaves, it’s called many cases at the Supreme Courts are eight or nine times it’s been affirmed by the Supreme Court.

What do you think of Gensler’s answers? Rep. Torres sounds pretty convincing, doesn’t he? Of course he does, he is basing it all on a fallacy. If they didn’t sound so convincing at first glance, they wouldn’t survive as fallacies!

We put Gensler’s answer in the same category as when he was asked whether Ether is a security or commodity. The much firmer and correct answer would have been that the security or commodity narrative is a myth and something can be a security and commodity at the same time. That would have likely prevented the repeated attacks by Chair McHenry (which weren’t wholly unjustified).

Similarly, the much firmer and correct answer to Rep. Torres’s question would have been that what Rep. Torres is saying tells us absolutely nothing about whether or not secondary crypto transactions are investment contracts, or, how the Howey test should apply in the case of secondary crypto transactions.

People are generally very critical of Gensler. Unlike those people, we don’t think his intentions are bad. We feel that he actually cares about investor protection. The problem is the road to true investor protection is a toll road, and the toll one needs to pay is coming to a consensus on the definition of investing. Until and unless the SEC comes out and says something along these lines, no real progress will be made and it will be the American public that will be hurt.

Sure, the SEC can win a few cases here and there. But even if they win, it will be for the wrong reasons. Worse, they put themselves in a vulnerable position by not having firm positions on many important questions, such as: 1) What is investing? 2) Is the security vs. commodity distinction real? 3) Is Bitcoin a security? 4) How does the Howey test apply in the presence of non-cash-flow-generating assets? Etc. Maybe one day, the SEC will appreciate that the path to principled wins in the investor protection space starts with offering a formal definition of the word investing.

What will happen now? We’ll see how much airtime the arguments by the legal scholars will receive during today’s hearing, and how the SEC will respond to those questions. As a reminder, we have filed our own amicus brief in the case, which you can find here. As you might expect, we talked about the base rate fallacy in our brief as well. Will the Court consider our arguments? We shall see.