Crypto is the New Orange

Except… Can you savor it, squeeze it or flame its peel?

At the heart of the ongoing crypto regulatory debate lies a crucial question: Are crypto tokens securities? While we believe that they can often be deemed investment contracts and, consequently, securities, this perspective might not be the most popular. Yet, we are very confident about the strength of the rationale we use to support our point of view, and we started drafting a law review essay on this topic.

Within our essay, one of the sections will likely be dedicated to dissecting the implications of the opposing stance: the position that the tokens themselves are not securities. Here are the critical questions: Does that position pave the way for logical and comprehensive outcomes? Does it lead to satisfactory answers to hard questions? Does it align with the fundamental objectives set by Congress? Should all these questions yield negative answers, it would cast substantial doubt over the validity of the alternative position that crypto tokens are not securities.

We have already elaborated on one of the implausible implications of the Torres decision, namely the decoupling of stocks from cryptocurrencies. We’ve underscored the inadequacy of the phrase “investment contract” as a catch-all term if it fails to encompass the most foundational financial instrument - stocks. Over the course of this month, our exploration continues, dissecting additional dead ends and illogical conclusions. Today, we set our sights on a colorful yet illustrative topic: Oranges.

Let’s embark on a thought experiment: When you visit the grocer to buy oranges, what motivates your decision? We suspect that in substantially all cases, it’s the intent to consume the fruit. You can peel and savor it, squeeze it and make fresh orange juice, or even flame its peel to enhance an Old Fashioned.

What motivates your decision when you buy crypto tokens? Does a similar narrative apply?

On September 29, 2021, Ripple’s Chief Legal Officer, Stuart Alderoty, tweeted an image, perhaps unaware of the cultural resonance it would ultimately attain within the crypto community:

The orange evolved into a symbol, championing the notion that if oranges themselves are not securities (as opposed to the orange grove arrangements in Howey), then neither would be the crypto tokens. This interpretation has garnered support within the pro-crypto circles. Before we argue why that analogy sits on a shaky foundation, let us share with you a few of these orange references.

In November 2022, the New Hampshire District Court ruled in favor of the SEC in SEC v. LBRY, Inc., and one Twitter user posted the following:

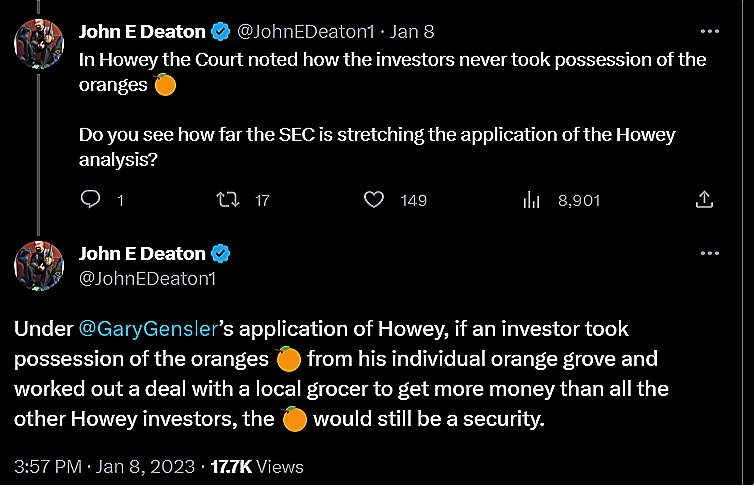

John Deaton likes this orange interpretation, too. Here is a sampling of his tweets:

He then continued with another Tweet:

The Twittersphere (now X) is full of these orange tweets! Here is one that John Deaton recently posted after the Ripple decision in mid-July:

The orange references are not limited to X (f/k/a Twitter) images either. An article published in the New York Law Journal on August 4, 2023, titled The SEC’s Materially False Statements on Crypto questioned the SEC’s assertions regarding crypto tokens, reinforcing the notion that oranges and tokens are comparable.

Jeffrey Alberts, partner at Pryor Cashman wrote:

In Howey the Supreme Court did not rule that the oranges (or the orange groves) were investment contracts. An orange is not a “contract, transaction or scheme.” So, while an orange can be the subject of an investment contract, it cannot itself be an investment contract. Oranges aren’t securities.

Why can’t the orange itself be an investment contract? On the one hand, there is no inherent barrier to that possibility. At the same time, the claim does not sound farfetched at first glance either, which is precisely why people, perhaps opportunistically, insist on the analogy. In any event, this is what we suspect is happening:

The statement that oranges can’t be securities is essentially the conclusion of an underlying Howey analysis, likely conducted subconsciously.

When purchasing oranges, the intent is clearly consumptive - to eat, squeeze, or utilize them in various ways. This contrasts significantly with the varied motivations for purchasing crypto tokens, where utility and speculative gains intermingle.

Can anybody assert, with evidence rather than mere unsupported claims, that a substantial majority of crypto token-use is for utility rather than speculation? While this might be true for some tokens in the future, the current data and anecdotal evidence paint a different picture today.

Currently, the “pro-orange” crowd fails to provide this level of substantiation. Instead, they erroneously draw parallels between a fruit that largely belongs to our kitchens and a financial construct that largely belongs to our (digital) wallets.

A couple of very important factual differences should help drive this point home:

Oranges aren’t traded alongside stocks on exchanges.

We have already observed the perceived equivalence between stocks and crypto, particularly from a finance standpoint. We also discussed it in the context of legal implications in a prior blog post. To that end, we like quoting a 2021 article by Fortune: Your father’s stock market is never coming back:

With a Robinhood account, your first exposure to cryptocurrencies does not frame them as an unproven alternative to stocks. The two stand on equal footing. Coke and Pepsi. Feel like trading one or the other? Have at it, no difference. This is radically different from the experience of the Gen X and boomer investors … The generation creating the new conventions of the investing landscape views stocks and crypto coins as interchangeable. (emphasis added)

As far as we are aware, there is no exchange for oranges, where they are traded alongside stocks (one can of course trade orange juice futures for risk management and speculation purposes, subject to robust financial regulation).

Oranges aren’t promoted, nor perceived as investment opportunities.

It’s not just exchanges like Coinbase that promote the concept of “investing” in crypto. It’s also respected asset managers, personal finance experts, top business schools, distinguished academics, and everybody in between. Even the crypto critics call it an investment. It is clear that cryptocurrencies receive extensive promotion as investment avenues, so much so that, across the aisle on our sister finance blog, we dedicated an entire month (June 2023) to the misguided view that crypto purchases constitute investing.

The stark contrast with oranges is undeniable. Simply Google-search crypto investing and you’ll see strategies, books, subreddits, etc.). Now, Google-search “orange investing.” You’ll quickly see that it hardly compares to the plethora of resources available for crypto “investments.”

Can we truly know the individual motivations behind crypto purchases? Understanding individual intent has been a longstanding Achilles' heel in Howey’s "expectation of profits” prong, which, by and large, focuses on the intent of the purchaser. However, as we noted here, the motivation of the buyers is not observable, so the second-best checkpoint becomes the intent of the seller/promoter. It is crucial to understand that the focus on the seller/promoter is not so much what Howey is trying to accomplish, as much as it is a necessity. In a perfect world, if one could fully observe the buyer’s motives, how the seller/promoter markets the product wouldn’t really carry much weight, if at all. Mark Cuban thinks some of that information may be gleaned by looking at the blockchain, which, if true, may inform how Howey is applied in some cases.

So, why do people purchase crypto? While some utility purchases do exist, the dissimilar circumstances make the orange analogy untenable. Concluding that oranges aren’t securities doesn't directly imply the non-security characterization of the tokens themselves. It merely suggests that, based on the totality of circumstances, oranges clearly fail the “expectation of profits” prong of Howey. Certain crypto tokens may also fail this prong in the future (maybe even today based on the facts), but the orange analogy simply lacks a principled basis and will likely fail when used properly in a court of law based upon precedent.

In essence, the orange analogy falls short on logic. Ultimately, this discourse concerning oranges appears either misleading, or at worst, a disingenuous attempt to muddy the waters.