Sports Markets Are Heating Up

Part IX: Kalshi goes global, courts go local: The preemption puzzle deepens

At this point, we’ve stopped pretending prediction markets might slow down. So let’s give you the two major developments from the past few days, then return to the Maryland decision.

First some Kalshi news.

Kalshi just closed a $300 million Series D round led by Sequoia and a16z, valuing the company at $5 billion. They also announced plans to go international–expanding to more than 140 countries–and are now the largest prediction market in the world.

The a16z press release included this gem:

Every question—whether about politics, economics, technology, sports, or the weather—becomes an investable asset.

Uhm, no. Prediction contracts are not investable assets; and in their current form, they never will be.

What’s happening is clear if you know where to look: We’re witnessing the 21st-century version of subliminal advertising in finance. The word “investment” floats around like a ghost–mentioned in the same breath as prediction markets, popping up on websites, disappearing, then reappearing in some other form. It’s subtle, but important. We dedicated yesterday’s F27 (our sister blog) to this phenomenon–check it out.

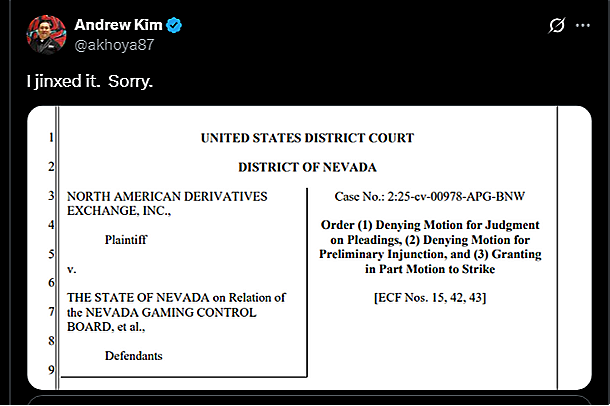

And, some more news, out of Nevada:

If you’d like to follow the case entries, view the CourtListener docket here. If you’re only interested in the opinion you can find it here (PDF).

We’ll spend time unpacking various aspects of this opinion in future posts, starting with our executive summary.

Executive Summary (Nevada Opinion)

Judge Gordon does not address three necessary components:

Whether a sporting event is a commodity;

Whether the outcome of a sporting event could count as a contingency; and

Whether sporting events are associated with financial, economic and commercial consequences.

Instead, he sets aside these three critical statutory questions and limits his analysis to whether sports event contracts are swaps. He concludes–incorrectly, in our view, though ultimately inconsequentially–that they are not.

In doing so, he also reversed himself. (Yes, this is the same judge who granted (PDF) Kalshi’s motion for preliminary injunction on substantially the same facts just a few months ago.) He offers no explanation for the reversal.

Bottom line: We think it is highly likely that this decision will be reversed on appeal, and if not, is unlikely to prevail when the Supreme Court looks at it.

Now, we’re finally back to the Maryland opinion.

Before Nevada, Maryland stood alone as the only state where the federal preemption argument was rejected. Early on (during oral argument), Judge Abelson signaled some skepticism toward the preemption stance, laid out eight reasons to support his stance and eventually sided with the state. In Part V of this series, we explained–on a high level–why the Maryland decision is likely an overreach. In Part VI, we covered Reason #1. Then came a barrage of prediction market news, and we detoured from our Maryland coverage for a couple of weeks.

Today, we explore Judge Abelson’s Reason #2:

Second, the CEA’s express preemption clauses, 7 U.S.C. § 16(e)(2) and (h), further confirm the absence of congressional intent to preempt state sports-betting laws.

Here, Judge Abelson dives deeper into the statute. Let’s follow him to § 16(e)(2) (We’ll save subsection (h)--which deals with insurance–for another day, but similar arguments apply).

Here’s what § 16(e)(2) says, under the heading “Relation to Other Law, Departments, or Agencies”:

This chapter shall supersede and preempt the application of any State or local law that prohibits or regulates gaming or the operation of bucket shops (other than antifraud provisions of general applicability) in the case of—

(A) an electronic trading facility excluded under section 2(e) [1] of this title; and

(B) an agreement, contract, or transaction that is excluded from this chapter under section 2(c) or 2(f) of this title or sections 27 to 27f of this title, or exempted under section 6(c) of this title (regardless of whether any such agreement, contract, or transaction is otherwise subject to this chapter).

Judge Abelson then says:

Congress’s decision to expressly preempt state gaming laws for certain transactions and state-insurance laws for swaps—compared to its silence as to all others—is strong evidence that Congress did not intend to regulate so comprehensively as to exclude all state law.

Setting insurance aside, what do we make about this alleged partial preemption of state laws?

To decipher what the statute says, we must rewind to 1974.

The Treasury Amendment

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974 was a game changer. It’s the Act that established the CFTC. In parallel, the reach of federal law expanded dramatically. It wasn’t just about wheat, corn and barley anymore–it was about financial indices and many things adjacent.

The evolution would culminate with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which introduced the concept of excluded commodities. Practically everything under the sun became a commodity. That’s how sports came in. And elections. And everything else. Understanding that evolution is relevant to what’s happening today but let’s stay in 1974 for now.

The Treasury was concerned