Sports Markets Are Heating Up

Part VIII: Preemption, swaps, sports futures & the CFTC’s tightrope

Yes, we know. We still owe you our deep dive on the Maryland decision, but the news keeps coming.

First the big one:

We’ve covered this in great detail over at our sister blog, Finance 2027, so you might want to start there and circle back. In other news:

→ The District Court in Nevada thinks sports event contracts are not swaps.

→ Brian Quintenz is officially out of the race for Chairman of the CFTC.

→ Tarek Mansour (Kalshi) and Shayne Coplan (Polymarket) were on a panel. Until two days ago, that didn’t seem particularly consequential. Now it does. More than anything, it feels like a “welcome to the club” moment for the new money. With each passing day, it becomes clearer that the confusion in law and finance will likely get worse before it gets better.

→ Polymarket did the expected: It self-certified moneylines, point spreads and over/unders. When Eris Exchange did the exact same thing a few years ago, it went nowhere. Seeing the writing on the wall, ErisX had no choice but to withdraw the contracts. The laws haven’t changed. What do you think will happen this time?

→ Six senators sent a letter to the CFTC (PDF), including two from our home state of California and one from Utah. We have a feeling these two states will be pivotal in determining how far back the sports gambling genie gets stuffed into the bottle when the Supreme Court decides to intervene (yes, it’s a matter of when, not if).

-- Last, but not least, the CFTC finally chimed in on sports event contracts–in the form of an Advisory.

Perhaps the most notable bit from the Advisory:

FCMs, IBs, DCMs, and DCOs should provide customers, market participants, and clearing members with regularly updated information, including information based on any States in which they operate or engage in activity, to ensure that such customers, market participants, and clearing members understand the possible effects should State regulatory actions or ongoing or new litigation, including enforcement actions, result in termination of sports-related event contract positions.

Is it possible the CFTC doesn’t believe federal law preempts state law? Andrew Kim raised that possibility:

It may be that the CFTC is simply being cautious about what could happen if prediction markets lose their preemption fight against the states.

But the advisory makes me wonder whether the current CFTC (i.e., a CFTC without new leadership) will support sports prediction markets in that preemption fight—or whether it will simply stay above the fray. A CFTC exercising this kind of prudence about parallel authority may not share the view of prediction market operators that the agency’s “exclusive” jurisdiction should exclude the states.

Here’s the thing: It’s practically impossible for the CFTC to “stay above the fray.” The CFTC regulates the trading of commodity futures. Various DCMs are self-certifying sports event contracts almost daily. Even doing nothing–declining to initiate review under the authority granted by Congress–is a decision.

Speaking of which, wasn’t the CFTC supposed to conclude its review of the Nadex/Crypto.com sports event contracts?

Sooner or later, the CFTC is going to find itself back in court. There’s simply too much at stake. We’ve long believed it will likely be an APA challenge, and Brogan Law pointed to that possibility as well. Who the challenger might be is a fantastic thought experiment. Could it be California or Utah?

If Andrew Kim’s point is that the CFTC won’t officially take the position that federal law preempts state law–and will simply continue to do nothing–we don’t necessarily disagree. But we don’t believe staying above the fray is viable in the long term. Sooner or later, they’ll be forced to take a position.

If you distill the issues to their core, just three questions matter:

Question #1: Is Sports A Commodity?

Remember, we asked this question 12 years ago…

The answer? It came from Brian Quintenz eight years later (in 2021):

When we think of commodities, we think of tangible things. Oil, corn, gold. There are intangible commodities too, most of which have a connection to the financial system, like a broad stock index (S&P 500) or a borrowing rate (LIBOR). But what about an event? An election? Whether the Summer Olympics will occur in Japan? A …. football game? Those, too, are commodities! (emphasis added)

Brian Quintenz is not just a random voice. He’s a former CFTC Commissioner, was the presumptive CFTC Chair until recently, and currently sits on Kalshi’s Board of Directors–a position he’ll likely retain now that his nomination is officially withdrawn.

Is Quintenz correct that sports is a commodity? Absolutely. Why would it not be?

→ The CFTC itself argued in court, just a couple of months ago, that the definition of commodity is much broader than agricultural commodities.

→ Michael Philipp, who spent time both in practice and at the CME wondered whether sports would be a commodity back in 2007, before Dodd-Frank. (See Michael Philipp, Excluded Commodities--What Is Included. Futures Industry 2007. Originally published by Futures & Derivatives Law Report.)

→ Paul Architzel, retired Senior Counsel (WilmerHale) and the architect of the CFMA of 2000 had an article out back in 2006, wondering the same; also before Dodd-Frank. (See Paul Architzel, Event Markets Evolve: legal certainty needed, Futures Industry (March/April 2006)).

→ Former Commissioner Berkovitz agreed as well, and cited Architzel. See footnote 15 in his ErisX statement.

→ And back in 2008 when we were discussing a sports futures product with the Division of Market Oversight, their view was that sports was an industry, just like any other (granted, our proposed futures product wasn’t contingent on game outcomes, but still).

→ And in case one might be inclined to argue that excluded commodities are not commodities, that’s not true, either. Excluded commodities are a class of commodities; and ultimately they just highlight the shifting focus of the futures industry away from its agricultural roots to become much more inclusive, encompassing a wide range of financial and event-based instruments. As former Commissioner Berkovitz observed (also in footnote 15): “The nomenclature is an anachronism.” The CFTC itself is on the record saying these same things (when they were dealing with InTrade).

So, Brian Quintenz may not be the right person to lead the CFTC (that seems to be the Administration’s thinking, given his nomination was pulled), but he is right on this one. Sports is an excluded commodity, and therefore a commodity. And once that view is accepted, the CFTC gains exclusive jurisdiction.

But wait… Didn’t we just tell you that the District Court in Nevada, in denying Crypto.com’s motion for preliminary injunction, ruled that sports event contracts are not swaps? Can sports event contracts not be swaps but still qualify as futures contracts with sports as the underlying commodity? If yes, what happens?

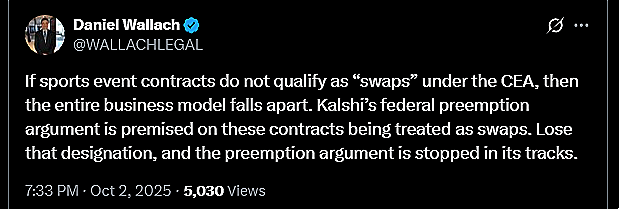

Dan Wallach believes that if they’re not swaps, the CFTC loses jurisdiction.

We disagree, however. Our quick reactions to the Nevada ruling were:

→ The distinction between outcome and occurrence seems artificial; and

→ One doesn’t even need sports contracts to be swaps for the CFTC to have jurisdiction.

Now let’s dive deeper and look at what the statute says:

The Commission shall have exclusive jurisdiction, … with respect to accounts, agreements… and transactions involving swaps or contracts of sale of a commodity for future delivery (including significant price discovery contracts). (emphasis added)

The key word is “or.” Swaps entered the statute via Dodd-Frank. Previously, the statute already included: “...transactions involving contracts of sale of a commodity for future delivery…” If sports is a commodity–analyzing the CFTC’s litigation positions, its former commissioners’ views on the record and various practitioner/scholar’s positions in their entirety, this is by far the most plausible outcome–it was already a commodity before Dodd-Frank was enacted. So concluding that sports event contracts are not swaps–even if correct–proves nothing.

We believe sports is an excluded commodity. But let’s consider a hypothetical: Imagine the CFTC takes the position that i) sports event contracts are not swaps; and ii) sports is not an excluded commodity; at that point, the CFTC effectively washes its hands of the matter (though an APA challenge would still be in play). That would likely mean state-regulated sports betting continues, but Kalshi and Polymarket are effectively finished (Surprise: The majority of Kalshi’s business is sports.)

Question #2: If Yes, Can the CFTC Allow It?

If sports is an excluded commodity (it is), and the CFTC has jurisdiction (it does), then the next question is whether sports event contracts are contrary to public interest. That determination, by law, lies with the CFTC. So they’ll need to take a position–sooner or later.

There was once a concept called the economic purpose test. Congress formally abandoned it in 2000 with the CFMA. The CFTC held on for nearly another quarter century. Why? Because it had to. U.S. commodity futures regulation is built on a foundational principle: Futures contracts should only be allowed when there’s an economic purpose–otherwise, they are just a vehicle for gambling. Whether formally codified or not, the CFTC continued to rely on the spirit of the economic purpose test to evaluate product submissions (nearly all of which were self-certified). Then, inexplicably, the CFTC abandoned the test in 2024 during litigation with Kalshi. The result? Kalshi won, and election contracts became a reality.

What mechanism does the CFTC now have to determine whether an event contract constitutes gambling? If you believe the CFTC, none. It was Brian Quintenz who planted the seeds for that viewpoint. He was in the minority at the time; former Commissioner Berkovitz and the majority of the Commission still relied on the test–which was the basis for the planned rejection of ErisX’s contracts.

We continue to believe the economic purpose test is alive and well. We believe the word “gaming” in the Special Rule actually means “gambling,” and the assessment tool is the economic purpose test. We also believe the Court of Appeals was poised to rule along those lines, but the CFTC dropped the appeal–so we won’t know, at least not until the next litigation.

Even if “gaming” doesn’t mean gambling and the economic purpose test is no more, someone still needs to explain what the word “gaming” does. Kalshi and the Commission actually agreed during litigation that the gaming prong includes sports events contacts. Moreover, the CFTC’s own regulations prohibit gaming contracts, a puzzling backdrop against the CFTC’s inaction and something that Dan Wallach loves pointing out. The six Senators we mentioned earlier wonder the same thing–it’s the very first question in that letter.

Yet after Kalshi took the position that sports event contracts were out of bounds, it did a complete 180 and self-certified its sports event contracts just a few days later. The CFTC didn’t even bother to initiate a review. And here we are.

If this case reaches the Supreme Court–and it likely will– get the popcorn ready. There will be puzzled looks when the Justices realize that current and former CFTC commissioners can’t agree on the status of the economic purpose test or the meaning of “gaming” under the Special Rule. With Loper Bright under their belt (opinion), we expect the Justices won’t give much deference to the CFTC (we dedicated a full section to Loper Bright and how the CFTC’s actions can be evaluated through that lens in our NJ amicus brief) and will interpret the law as they see fit. If they do, their thinking will likely align with the view that was in the process of being formulated by the Court of Appeals–and under that scenario, the sports event contracts are out.

Question #3: Is There Room for States To Do Anything?

The analysis under #2 creates two possible scenarios:

Sports event contracts are good to go (because either the economic purpose test no longer applies, or they don’t involve gaming even without the test); or

They’re not.

So what can states do under either scenario?

The answer, again, comes from Brian Quintenz:

Got that? All events are commodities, which means all contracts on future events are commodity futures contracts, which means all future event contracts need to be traded on a regulated and registered futures exchange. But if the Commission deems any event contract that involves one of the enumerated activities to be contrary to the public interest, that contract is banned from trading on any registered futures exchange. The contract cannot trade anywhere else either since it is still a commodity futures contract and, if traded off of an exchange would be illegal.

So, if sports event contracts are kosher (a very big if), they must be traded on a registered exchange. If they’re not, they can’t trade anywhere.

The critical conclusion:

Either way, there is no room for state-regulated sports betting.

You may laugh this off. You might note that Kalshi didn’t even go that far, and argued co-existence is possible. First, that doesn’t mean Kalshi is correct. Second, nothing prevents them from making that argument and consolidating power if they emerge victorious from the current court battles. This company is clearly not afraid of a 180.

You might also say the CFTC signaled the possibility of a parallel structure with its Advisory. That doesn’t mean they’re correct either–and, if that is truly their position, we don’t think their story would hold together in any meaningful way.

So, feel free to reject our reasoning–but do so at your own peril. The off-exchange trading prohibition is real, and Congress has repeatedly reinforced that principle. Taking the alternative position means ignoring a century of congressional guidance. Will the Supreme Court side with Congress–especially now that Chevron is gone–or will it defer to a regulatory agency that keeps shifting its stance? We think the answer is clear.

Final Thoughts

The current litigation is unfolding in isolated silos, each focused on narrow legal questions. We don’t believe that’s how the Supreme Court will approach it. Instead, everything will be on the table–with the three questions we laid out in this post forming the core inquiry.

In any event, while these developments create even more uncertainty on many fronts, they also clarify the arc of the sports event contracts narrative:

→ The preemption question is becoming more important by the day.

→ The only decisions to date that ruled against federal preemption are Maryland and Nevada.

→ Therefore, the arguments these two courts relied on are becoming more important.

With that, we hope to dive into the technicalities of the Maryland decision next time. And then the Nevada opinion will be on tap.

Prediction markets, please allow us a few days of silence!