Backdooring Sports Gambling is Precisely What Congress Wanted to Prevent

Our arguments have been in front of the Supreme Court all along

A fundamental inaccuracy has been making the rounds, and it’s time we set the record straight.

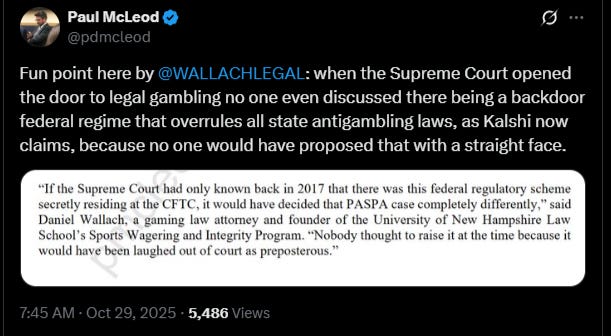

Here is one version of it:

It originates from Dan Wallach, and more specifically, from this podcast:

We’ve queued the video to the relevant segment so you can jump straight into the context. Prefer words instead? Let’s walk through it:

And then the Murphy case… Murphy v. NCAA which led to the overturning of PASPA. If the U.S. Supreme Court had only known in 2017 and 2018 that the federal government was already providing a regulatory framework for sports betting, the leagues would have won that case. The state of NJ won simply because PASPA only commandeered the states without providing any federal scheme of regulation or deregulation. So, if the argument that Kalshi and Polymarket and Crypto and Robinhood are advancing today is true, it was also true as far back as 2010 and it was true throughout the entirety of the PASPA litigation and nobody, not a soul raised it. Which means, it’s all a bunch of BS, and it’s fabricated after the fact, to justify and only through clever lawyering has Kalshi even gotten this far.

If there’s a single 60-second podcast segment that could shape the future of sports gambling in America, this might be it. Wallach is as impassioned as we’ve ever seen him, and at first glance, his argument appears airtight.

But here’s the problem: Beneath this delivery lies several statements that are misleading or flat-out inaccurate.

Last week we addressed why the “federal regulatory framework” phrase is misleading. It should have been labeled the “federal jurisdictional framework.” The distinction is absolutely crucial.

What about the Supreme Court angle? It’s simply not true. The Supreme Court had already known because we’ve told them twice already.

It’s disappointing to see Ryan Rodenberg, generally a calm, measured source of solid insights, jumping on the bandwagon:

As a close observer during the entire pendency of the SCOTUS sports betting case involving New Jersey, I did not recall the Supreme Court — or anyone else involved in any portion of the litigation spanning seven years from 2012-18 — ever mentioning how federal laws pertaining to commodities permitted sports wagering.

The implication? Since the Supreme Court didn’t mention it, Kalshi’s preemption argument lacks merit.

To support this, Rodenberg offers a partial list of others who never raised the issue around the “role of the CEA, Dodd-Frank or CFTC regulations in the context of sports betting from 2012-18”:

Dozens of amici — including me — who filed briefs at various stages from the perspective of industry stakeholders, state law enforcement, or academia…

Literal truths that mislead in a broader context are the most dangerous kind.

So what’s the issue here?

First, even if no one mentioned it, that doesn’t mean the argument lacks merit.

Second-and more importantly–at least one amici mentioned it, us.

After laying his groundwork, Rodenberg offers a prediction:

A majority of the SCOTUS justices who decided Gov. Murphy v. NCAA, et al. will likely still be on the Supreme Court bench in two to three years. They would have to ponder whether they overlooked the novel argument that Congress authorized sports betting in all 50 states to flow through companies registered with the CFTC instead of regulators in states that have legalized sports wagering.

Funny word choice–”novel.”

We’ve heard that adjective before. It’s exactly how a former prosecutor and adjunct law professor described our amicus brief (PDF):

Finally got around to reading your amicus brief in Christie v. NCAA. Novel and clever. Well-done. I fear the Court may not grasp what you’re saying, but it won’t be because it’s not well-said.

But the broader issue with Rodenberg’s framing?

It’s how he characterizes the argument: “Congress authorized sports betting in all 50 states.”

Our argument may have been novel, but it was certainly not that.

We argued that sports is a commodity, and therefore sports bets are commodity futures contracts, and finally, that means federal jurisdiction applies. We even addressed how the CEA interacts with other federal laws.

Ultimately, Wallach and Rodenberg are echoing the same sentiment–one that also underpinned the Maryland ruling.

Since Congress couldn’t have authorized sports gambling while simultaneously disallowing it via PASPA and the Wire Act, there cannot be federal preemption. But that contradiction disappears immediately the moment you distinguish jurisdiction from regulation. With the CEA, Congress didn’t authorize sports gambling, it simply reinforced its opposition to it.

Perhaps Rodenberg likes the idea of nationalized sports gambling:

The article he referenced is a thoughtful hypothetical–imagining Congress stepping in to regulate sports gambling on the heels of a fictional sports gambling scandal.

And Rodenberg is absolutely entitled to that view.

But here’s the thing:

If America wants to legalize sports gambling and wrap it around federal regulation, it must do so through the legislative process. Only then can all the infirmities that come with the existing laws–the CEA, the Wire Act, state gambling statutes, etc.–be properly addressed and reconciled.

Backdooring sports gambling is precisely what Congress intended to prevent. To be more clear, not allowing entertainment futures on any platform is what Congress wanted to accomplish. Sports gambling falls under that category and we must hold our nation’s watchdogs accountable.

Will Congress have the votes?

We doubt it, but if they do, the country must live with the outcome of a democratic process.