Congress Didn’t Blink

Jurisdiction vs. Regulation: A critical distinction that clarifies the CFTC’s role in sports gambling

Of course, there is news.

→ President Trump’s social media platform, Truth Social, has partnered with crypto.com, enabling Truth Social users to place a bet within its app.

→ Illinois warns sportsbooks about prediction markets.

→ The Massachusetts case returns to the state court.

Speaking of Dan Wallach, the sport betting and gaming lawyer, he was on a podcast last week…

It’s a good watch and it happens to touch on a topic absolutely instrumental to the future of sports gambling in America.

Jurisdiction vs. Regulation

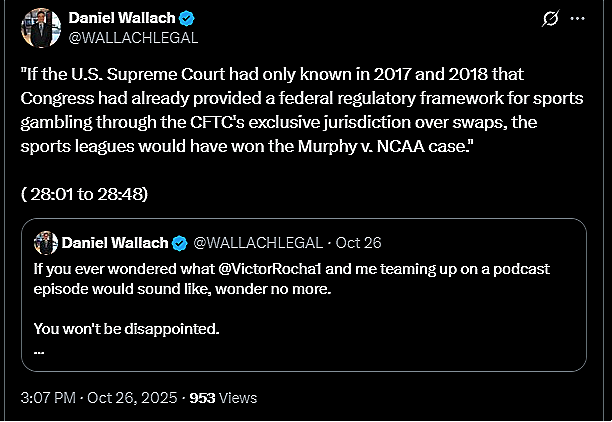

Here’s Wallach posting what he thought was a rather important nugget from the podcast.

It is rather important. The key phrase: “federal regulatory framework.”

Wallach seems to assume that sports event contracts must be regulated by someone, either the states or the federal government via the CFTC (we’ll set tribal jurisdiction considerations aside for now). Judge Abelson adopted the same assumption in his Maryland decision.

But the legal issue here consists of three questions that must be taken up holistically. We just offered this framework in our sister blog, F27:

We need to determine jurisdiction (based on the laws);

Whoever has jurisdiction then needs to decide whether the activity should be regulated or prohibited; and

Whoever is deciding, needs a standard for that decision.

Let’s tighten that up for memorability:

Question 1: Jurisdiction - Who decides?

Question 2: Allow/regulate vs. prohibit - What is the decision?

Question 3: Evaluation framework - How is the decision made?

There are two ways to gamble in America. The stock market? No, that’s a misnomer. And no, it’s not crypto either.

One can gamble by playing games. One can also gamble through futures markets. Fortunately, that three-question framework applies to both. Unfortunately, there’s very little agreement on how it applies to futures markets.

Let’s start with games, because that’s the straightforward application. Our answers:

Answer 1: States;

Answer 2: Allow/regulate games of skill, allow/regulate or prohibit games of chance; and

Answer 3: Use the skill vs. chance spectrum (first), and then, if desired, the legislative process (second).

These aren’t just our answers, they’re pretty much everybody’s. Take, for example:

Determination of whether a (pay-for-play) skill game (with prizes) is a permitted game as opposed to a prohibited game (of chance) is based on the relative degrees of skill and chance present in the game.

Of course there will be disagreement on exactly how much skill a game involves (poker, anyone?). There is also the question of how much skill is enough to make a game a game of skill. States place the skill marker at different spots on that spectrum; some apply the predominance test, others rely on material element test, etc. But the framework itself, dating back to British law, is firmly set in stone.

Then, once the characterization is made–game of skill vs. game of chance–games of skill sail through and games of chance still get another bite at the apple. They can still be allowed and regulated if the legislature decides that the benefits (e.g., tax revenue) outweigh the costs (e.g., addiction). As the Supreme Court stated in Greater New Orleans Broad. Ass’n, Inc. v. United States:

But in the judgment of both the Congress and many state legislatures, the social costs that support the suppression of gambling are offset, and sometimes outweighed, by countervailing policy considerations, primarily in the form of economic benefits.

If allowed and regulated, the residents of the state, no matter what their moral stance is against gambling, must live with the outcome. In the very least, there will be no confusion as to whether the activity is considered gambling or not.

How the framework applies to futures, and more specifically, the prediction markets, is literally the billion-dollar question. Our answers:

Answer 1: Federal;

Answer 2: Allow/regulate if it serves public interest, prohibit otherwise;

Answer 3: Economic purpose test

These are… just our answers and pretty much nobody else’s. Not because they’re unsound, but because taken together, they lead to a plausible conclusion: There can be no sports gambling in America, anywhere. (To get there, you also need to answer whether off-exchange futures trading is permissible. Answer that with a “not permissible,” and sports gambling unravels, unless, as Matt Levine puts it, legal realism trumps legal analysis.)

Take, for example, former CFTC Commissioner Brian Quintenz, whom we’ve cited frequently. He clearly believes that sports, like anything else, is a commodity:

When we think of commodities, we think of tangible things. Oil, corn, gold. There are intangible commodities too, most of which have a connection to the financial system, like a broad stock index (S&P 500) or a borrowing rate (LIBOR). But what about an event? An election? Whether the Summer Olympics will occur in Japan? A …. football game? Those, too, are commodities!

In case there’s any doubt, he doubles down:

Got that? All events are commodities, which means all contracts on future events are commodity futures contracts, which means all future event contracts need to be traded on a regulated and registered futures exchange.

So it’s clear that Quintenz agrees with our #1. The alignment does not stop there; he agrees with us on #2 as well:

First, it is not the case that trading an event contract with a binary outcome is automatically considered a bet, wager, or gamble from a regulatory perspective. The statute’s language proves that. If the statute assumed that participating in any event contract involved making a wager or gamble, there would have been no need for Congress to individually enumerate “gaming” as a distinct category of event contracts upon which the Commission could make a public interest determination.

Where the NYT opinion piece stumbles (“Next came prediction markets, which allow users to bet on anything — from Taylor Swift album sales to the weather — while avoiding the regulations that inhibit licensed gambling companies.”), Quintenz remains on solid ground. We fully agree: Not every single binary contract is a bet. Why would they be?

Which, of course, begs the question: How will we decide? After agreeing with Quintenz on #1 and #2, here comes the consequential disagreement:

As discussed extensively above in the Constitutional Concerns section C, the Order stated that the “legislative history” indicates Congress’s intent to “restore” the economic purpose test that was in use prior to the year 2000. The Order neglected to even give us a footnote to explain where in the legislative history this indication can be found. By a process of elimination described above, I assume it is the colloquy between Senator Lincoln and Senator Feinstein. This is, even by legislative history standards, very slim support. This lone conversation between two senators is not enough [to] resurrect what Congress as a whole previously removed.

It obviously is the colloquy, because there’s nothing else. That’s clearly not enough for Quintenz, even though he seems to favor the test:

This is not to say that economic purpose test is the wrong test. In my view, the economic purpose test would be a useful tool for the Commission to employ in analyzing new event contract filings. However, until Congress indicates that this is the test it required, we cannot say that it is the correct test.

Well… If that is not the correct test, and has not been since 2000, why was the legal and economic advice we received in 2007, when we proposed a sports futures contract (not based on outcomes) was that we need to demonstrate a bona fide business purpose? From the architect of the CFMA and former acting chair of the CFTC, no less.

Why did the movie box office guys go through a similar process? Why was there a congressional hearing, a public comment period (see footnote 27 in this Note and submitted comments on Cantor’s products), and then an almost-four-hour public meeting (PDF transcript, video)--all centered around economic purpose and hedging utility? What does it even mean to disregard the economic purpose test while still considering potential hedging utility? The economic purpose test, after all, is fundamentally about potential hedging utility. Why were the box office contracts approved on the basis that they allowed the participants to manage financial risks (before Congress outlawed them)?

Why did NADEX build a detailed dossier (PDF) and tout potential hedging benefits in 2011 on its proposed election markets, only to be denied three months later, on the grounds of… economic purpose (PDF)? Why did Kalshi itself devote significant real estate to an economic purpose argument?

Was all of that for naught? Hundreds of thousands of hours and who knows how many millions of dollars were spent demonstrating economic purpose, because somehow, everybody missed that the statute was repealed?

No, of course not. The explanation is much simpler.

The Commission is the gatekeeper, so mandated by Congress, in deciding which futures products should be allowed or regulated versus which ones should be prohibited. To make that decision, it has to rely on a framework. And, unlike games, there is no second bite at the apple: Once it’s determined that the products are contrary to public interest, that’s the end of the road for that product. Congress did not contemplate a marketplace for futures that are deemed gambling. Either you’re in, or you’re out.

Allow or prohibit? To make that decision, there must be a framework in place. Would anyone expect states to determine which games are gambling without resorting to the skill vs. chance spectrum? That would be simply unworkable. To avoid a similar fate, the Commission did what any reasonable decision-maker would do: it followed the spirit of the law. Until the Kalshi litigation commenced, that is.

If the Commission can simply wash its hands off the decision-making process because a statute is repealed and no alternative is offered, then something has gone terribly wrong. Sure, there’s a missing statute somewhere. Also true: It’s generally not ideal for agencies to resurrect statutes, that’s Congress’s job. But when the agency has its own workload to manage and feels it’s getting no help whatsoever from the text of the law, it is perfectly reasonable for it to lean into, in the CFTC’s own words (oral argument audio), 175 years of congressional intent of keeping gambling away from futures markets:

To build and maintain a thriving derivatives industry that is distinct from the gambling business has been the work of 175 years, and it’s important.

That’s the way to see it and that’s what Brian Quintenz is missing. The legislative history is not just the colloquy. That’s a side conversation that is attached to one piece of legislation: Dodd-Frank. But it stands atop a century-old Congressional mandate going back to the Grain Futures Act of 1922–and possibly even further back. As such, Quintenz’s view that the CFTC’s hands are tied doesn’t create tension with just the colloquy. On the other side of the scale is the foundational, century-old premise that futures markets are not designed with gambling in mind. That’s the wall his and similar arguments run into.

Let’s Bring It All Together

Here’s how we would summarize the positions:

Brian Quintenz

The Commission has jurisdiction over all event contracts. Some are good to have and some are not. Prior to 2000, the decision-making tool that helped the Commission to separate the wheat from the chaff was the economic purpose test, and I personally still like it. But since Congress took away that tool, the Commission cannot make these types of public interest determinations anymore.

Us

Indeed, the Commission has jurisdiction over all event contracts. Some are good to have and some are not. Between 1974 and 2000, there was an explicit framework–a recipe for how those decisions are supposed to be made; a recipe that even former Commissioner Quintenz appreciated. Congress took that recipe away without replacing it. But just like a cook who runs the restaurant kitchen still has to cook, even when the owner takes away the written recipes, the Commission must still determine which futures contracts serve the public interest (and which ones don’t) by making judgment calls–guided by precedent, economic purpose and institutional memory–even if the statutory cookbook is now missing a few pages.

Dan Wallach

Congress could have not possibly have allowed sports gambling through futures exchanges when it banned it elsewhere via the Wire Act and PASPA.

We see where Wallach is going with this, but disagree with his premise. Once the critical distinction between jurisdiction and regulation is acknowledged, what seems like an impossibility, turns into cohesive congressional intent that spans three generations.

The Impossibility That Goes Away

The conclusion is certainly solid. It would indeed be implausible for Congress to ban and allow something at the same time–pick your favorite case law quote here:

Absent persuasive indications to the contrary, we presume Congress says what it means and means what it says.

Wallach would likely agree. His main point is that it wouldn’t make sense for Congress to guide two diametrically opposite outcomes (allowing sports gambling while also prohibiting it) in different statutes:

[H]ow implausible it would have been for Congress to ban sports betting through the Wire Act and PASPA and at the same time tacitly allow it through an obscure and opaque commodities exchange. (emphasis added)

The outcome would indeed be difficult to reconcile–if Congress tacitly allowed it. It didn’t. In fact, it did quite the opposite: It reinforced the sports gambling prohibition. Legislative history on the special rule is thin, but the record we do have–the colloquy–clearly speaks to sports event contracts being prime candidates for prohibition in the futures markets. The CFTC itself must have understood it that way at the time, because why would you otherwise implement 17 CFR 40.11?

And again, we don’t agree it’s reasonable to view the colloquy as an isolated incident. It’s just one piece of legislative history in which the century-old congressional intent–to keep gambling away from futures markets–manifested itself. The intent is what matters.

And just like that… The tension disappears. Here’s how we would have phrased it:

The courts are finally addressing the issue of Congressional intent and realizing how plausible it was for Congress to reinforce the ban on sports gambling. They already had the Wire Act and PASPA, two statutes that, despite being enacted 31 years apart, fundamentally achieved the same goal. Now, Congress came to the realization that sports is a commodity (post-CFMA), knew about the self-certification process (also a product of the CFMA) and was certainly aware of event contracts, so it wanted to make sure the Commodity Exchange Act has its own provisions so nobody would attempt to rebrand sports gambling as a futures contact and try to backdoor it.

See how that flows? No tension, whatsoever. Just Congress reacting to developments and reiterating its intent.

One Question Remains

Who knew that sports gambling falls under the CFTC’s jurisdiction–and when did they know it?

Wallach seems to believe the idea came out of left field, almost invented by Kalshi (and other prediction markets) through clever lawyering. The public record clearly indicates otherwise. It’s been out there for at least twenty years–almost as old as the CFMA itself. From the CFTC to Congress to legal practitioners to academia, the notion that the CFTC has jurisdiction over sports markets has been hiding in plain sight.

Even the Supreme Court knew. How? We alerted them to the possibility. Twice. They simply decided not to engage.

In our next post, we’ll take you on a trip down memory lane.