Excluded Commodities, Swaps, and the Ross–Russ Parallel

How Congress collapsed the line between excluded commodities and swaps–and why that made it even harder for states to win on preemption

In our last couple of posts, we explored what “financial, economic, or commercial consequence” really means (Part I, Part II). Before moving forward, let’s briefly recap how that determination feeds into the jurisdictional analysis which we covered in Part II:

If the Lions winning or losing is associated with potential FEC consequence → It’s a swap and/or commodity futures contract.

If it’s a swap and/or commodity futures contract → The CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction.

If the CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction → Prediction markets operated by Coinbase, Kalshi and others can list and trade these contracts unless the CFTC blocks them.

It’s difficult to read the statute in any other way. Unsurprisingly, states have focused their attacks on the “financial, economic, or commercial consequence” prong. Consider Connecticut’s opposition brief to Coinbase’s motion for preliminary injunction:

Coinbase’s claim that sports event contracts relate to a “potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence” strains credulity. Even if it is possible to conceive of an event contract hedging against genuine financial consequences associated with the occurrence of a sporting event, those are not the contracts at issue in DCP’s cease-and-desist letter.

One might argue that a preseason game lacks meaningful “financial, economic, or commercial consequence.” What about the Super Bowl? Where exactly is the line drawn? We offered our resolution to this puzzle in Part II, so let’s set it aside and turn to a different set of questions:

Can a sports event contract fail to qualify as a swap yet still fall under CFTC jurisdiction?

Can a sports outcome fail to qualify as an excluded commodity, while a sports event contract still falls under CFTC jurisdiction?

Why is the statutory language for excluded commodities and swaps so similar in the first place?

These are not academic hypotheticals. These are live issues being litigated, including one of the most consequential battlegrounds: New York.

In that case, Kalshi v. Williams, Kalshi presented “excluded commodities” as an alternative route to exclusive CFTC jurisdiction:

Finally, even if the Court accepts Defendant’s reading of “swap,” the CFTC’s exclusive jurisdiction also extends to “future[s]” and “option[s]” on DCMs. 7 U.S.C. § 2(a)(1)(A). The events on which Kalshi’s contracts are based fall within the definition of “excluded commodity,” including any “occurrence, extent of an occurrence, or contingency” that is “beyond the control of the parties to the relevant contract, agreement, or transaction,” and “associated with a financial, commercial, or economic consequence.” Id. § 1a(19)(iv).

Predictably, New York pushed back:

First, Kalshi argues, without elaboration or analysis, that if its contracts are not “swaps,” they instead qualify as “option[s]” or “contracts…for future delivery” of a “commodity” under Section 2(a) involving “excluded commodities.” Reply at 3-4. This contradicts Kalshi’s self certifications and repeated representations that its contracts are “swaps.” See, e.g, ECF 35-1; ECF 81-1; 81-2. Moreover, Kalshi failed to apprise this Court that this argument was expressly rejected in KalshiEX, LLC v. Hendrick, 2:25-cv-00575, 2025 WL 3286282 at *10-12 (D. Nev. Nov. 25, 2025) (“Hendrick II”), a decision whose reasoning should be adopted here.

In plain English, Kalshi is saying: “If these aren’t swaps, fine–sports outcomes are still excluded commodities. I still reach the same destination by following a different road.”

New York responds: “But you’ve been calling these swaps all along, and Judge Gordon already rejected this argument.”

New York is walking on thin ice here. Kalshi’s argument that its contracts are swaps does not foreclose the possibility that sports outcomes can also qualify as excluded commodities.

Comparing the Definitions

Here is the relevant portion of the “excluded commodity” definition:

an occurrence, extent of an occurrence, or contingency (other than a change in the price, rate, value, or level of a commodity not described in clause (i)) that is— (I) beyond the control of the parties to the relevant contract, agreement, or transaction; and (II) associated with a financial, commercial, or economic consequence.

And this is the parallel language for swaps:

any agreement, contract, or transaction—(ii) that provides for any purchase, sale, payment, or delivery (other than a dividend on an equity security) that is dependent on the occurrence, nonoccurrence, or the extent of the occurrence of an event or contingency associated with a potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence;

There are really only two pairings to examine:

These look nearly identical–two sides of the same coin. One would need to get creative to manufacture daylight between them.

Here, the differences are more noticeable, but do they matter?

Parsing the Differences

Word order

The swap definition flips “commercial” and “economic.” This in itself is meaningless. It’s a list; order carries no substantive weight.What about the word “potential”?

The swap definition adds “potential.” What does that do?

➝ It broadens the scope;

➝ It effectively lowers the threshold from “is associated” to “may be associated.”

➝ It makes the “CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction” argument easier at the margin.

As Andrew Kim noted, the swap definition is incredibly broad. The addition of “potential” does not create a bright line between swaps and excluded commodities; if anything, it expands the statutory coverage even further.“Beyond the control of the parties”

This is the most meaningful difference. It appears in the excluded commodity definition but not in the swap definition.

Where else do we see this language? Gambling law.

Take New York as an example. New York’s Penal Law defines gambling as “stak[ing] or risk[ing] something of value upon the outcome of a contest of chance or a future contingent event not under [one’s] control or influence...” (bold emphasis added)

During the DFS litigation, David Boies (DraftKing’s counsel) made a clever point:

There are also certainly colloquial uses of the term gambling that are broader than New York’s definition (e.g., Pete Rose is alleged to have “gambled” by betting on his own team to win, although such a wager would clearly not be gambling under New York law); those uses, too, are irrelevant to this case. What is relevant to this case, and the only definition or usage relevant to this case, is New York’s legislative definition of gambling.

What Boies is really saying is that when Rose bet on his own team in games he played in or managed, he had the ability to influence the outcome. Not full control–there were other players on both sides–but influence nonetheless. And under New York law, that degree of influence is enough to avoid the statutory definition of gambling.

Is Boies wrong? If Kalshi is right, then yes, at least since 2010.

Why? Because of the jurisdictional chain:

If the Reds winning or losing is associated with potential FEC consequence → it’s a swap and/or futures contract.

If it’s a swap and/or commodity futures contract → The CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction.

If the CFTC has jurisdiction on sports event contracts, what Rose did would be characterized today as swaps.

Between 2000 and 2010, Rose might have escaped the CEA because the excluded commodity definition required the event to be “beyond the control” of the parties.

If he could influence the outcome, the event might not qualify as an excluded commodity for him, even if it did for everyone else (a bizarre result indeed).

There would still be a debate around where to draw the line–influence vs. control–especially in individual sports such as tennis, where a single athlete has far more control than a baseball player. Rose’s case is more nuanced–he could influence the outcome, but did he have control over it?

But under the swap definition?

There is no “control” language.

No carveouts.

No exceptions.

If sports event contracts are swaps, Pete Rose doesn’t get a pass–regardless of whether he was betting on his own team or not.

David Boies is not necessarily wrong in his analysis when he looks at it through the lens of New York law. He is wrong because he is using the incorrect lens. With federal glasses on, the analysis flips, and that is true for traditional sports betting, exchange wagering and daily fantasy sports.

Once again, Congress moved in a direction that makes CFTC exclusive jurisdiction easier to satisfy. The edge cases that may have once fallen outside the CEA now fall squarely within it.

Verdict

We don’t see a meaningful way to distinguish contracts on excluded commodities from swaps. On that point, while we don’t believe New York will ultimately prevail on its jurisdictional argument, we do agree with the following position it took in its brief:

“Excluded commodities” are defined under Section 1a(19)(iv) using many of the same terms as “swap” under Section 1a(47)(A)(ii)... see also Powerex Corp. v. Reliant Energy Servs., 551 U.S. 224, 232 (2007) (“identical words and phrases within the same statute should normally be given the same meaning”)

In other words, we don’t think Kalshi, or any prediction market, will lose the swap argument yet somehow win the excluded commodity argument. If anything, the statutory evolution signals continuity: Congress tightened the language over time and the direction of travel has consistently been toward broader CFTC coverage.

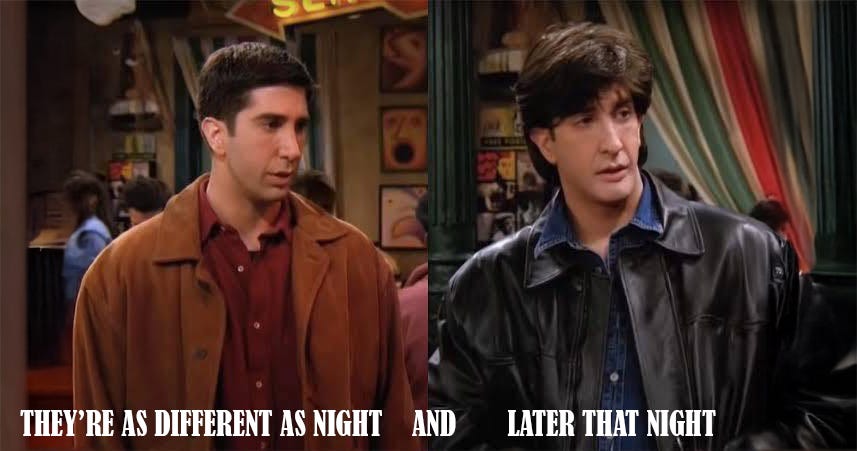

The difference between contracts on excluded commodities and swaps is the difference between Ross and Russ. In the episode titled The One With Russ (S2.E10), Rachel Green (Jennifer Aniston) dates a man who looks and sounds almost exactly like Ross–so similar that the joke is how impossible it is to tell them apart, delivered beautifully by Monica Geller (Courteney Cox):

They are as different as night and… later that night.

That’s the whole point here. You can strain to articulate distinctions, but functionally, they collapse into each other.