What Does “Financial, Economic or Commercial Consequence” Even Mean?

Part II: Why the naturally occurring vs. artificial distinction is the only workable limiting principle for prediction markets

3 Key Takeaways

Critical statutory term: “Financial, economic, or commercial consequence” (“FEC”) will shape the future of sports gambling in America;

Digging into the archives: A Nobel laureate in economics, indirectly, articulated the line-drawing principle courts are looking for; and

Verdict: FEC reaches far, but not infinitely. All naturally-occurring events (including sports) fall within its scope. Casino games do not.

Hope you all had a restorative holiday break. Now, back to work.

We are going to pick up where we left off: What does “financial, economic or commercial consequence” actually mean? This is significant. Congress introduced it in the CFMA of 2000. The CFTC never defined it nor provided guidance and today’s courts are wrestling with its scope in real time.

The latest battleground? Illinois, Michigan and Connecticut, where Coinbase launched an offensive, filing parallel complaints on December 18, 2025 (PDF versions: IL, MI, CN):

And, yes, FEC is front and center.

Coinbase’s filings repeatedly lean on the concept (the bullet points underneath are our short summaries):

Event contracts are derivative instruments that enable parties to trade on their predictions about whether a future event—which may relate to economics, or elections, or climate, or sports, or anything else of potential commercial consequence—will occur.

Event contracts allow trading on whether a future event (anything with potential commercial consequence) will occur.

The universe of potential underliers includes “commodities,” a term the CEA defines broadly to include virtually anything that can serve as a basis for trade or pricing—from tangible goods like wheat, oil, or gold to intangible variables such as financial indices, interest rates, or the occurrence (or nonoccurrence) of an event associated with financial, commercial, or economic consequences.

“Commodity” includes virtually anything that can serve as a basis for pricing, including events associated with FEC.

Congress expansively defined the term “swap” to include, among other things, any “agreement, contract, or transaction” that “provides for any purchase, sale, payment, or delivery . . . dependent on the occurrence, nonoccurrence, or the extent of the occurrence of an event or contingency associated with a potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence.”

Congress defined “swap” to include any contract dependent on an event associated with potential FEC.

As the CFTC has consistently recognized, event contracts are “swaps,” subject to the CFTC’s exclusive jurisdiction. That is because event contracts are binary contracts that pay out depending on the “occurrence [or] nonoccurrence” of a future “event or contingency.” 7 U.S.C. § 1a(47)(A)(ii). And the underlying event is “associated with a potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence.” Id. For example, the Lions winning (or losing) their next game has a clear economic and commercial consequence for stadium vendors, local communities, and team sponsors.

Coinbase even offers a sports example, arguing: the Lions winning or losing their next game has “clear economic and commercial consequence.”

With these latest filings, we are now pushing 30 lawsuits in just a handful of states. FEC is a major threshold question. The logic flows very clearly:

If the Lions winning or losing is associated with potential FEC consequence → It’s a swap and/or commodity futures contract.

If it’s a swap and/or commodity futures contract → The CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction.

If the CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction → Prediction markets operated by Coinbase, Kalshi and others can list and trade these contracts unless the CFTC blocks them.

So, here we are again where definitional clarity is of utmost importance. What does FEC actually mean?

Why This Question Matters

Most observers, including us, understand that FEC is a jurisdictional term, but it’s prudent to explore all possibilities. In our previous post, we dusted off a 2008 comment letter by Paul Architzel (CFMA’s architect) and considered whether FEC may have been intended as a modern replacement for the repealed economic purpose test.

We also connected that idea to our own regulatory journey with the CFTC. If the architect of the laws ends up being your external regulatory counsel who comments on those very laws, you listen. It’s our duty to give those thoughts some weight.

Ultimately, that interpretation runs into a wall: Common sense. In our post we wrote:

For starters, it seems slightly absurd to argue that snowfall at Detroit’s Wayne County airport is associated with potential financial, commercial or economic consequences and last year’s Super Bowl, an event watched by 127.7 million people, isn’t. And the Super Bowl ads? They’ve already sold out for 2026, fetching ~$7 million for a 30-second spot.

So, one can reasonably argue that the Super Bowl is associated with more financial, economic, or commercial consequence, compared to most other events underlying the contracts. Let’s take it a step further though. Does it mean there is more hedging around the Super Bowl contract than snowfall contracts?

The answer to that is a resounding no. A snowfall contract would have lower volume, but a relatively higher percentage of transactions would be for hedging (positive). The Super Bowl contract would have higher volume, but a relatively lower percentage of transactions, arguably de minimis (or none at all), would be for hedging (negative). In other words, the predominant use would be entertainment.

In short:

FEC is not a reliable proxy for hedging utility.

Congress cares about hedging utility, not entertainment value. If the FEC language was meant to replace the economic purpose test, it would be sloppy drafting, collapsing jurisdiction and permissibility into a single step.

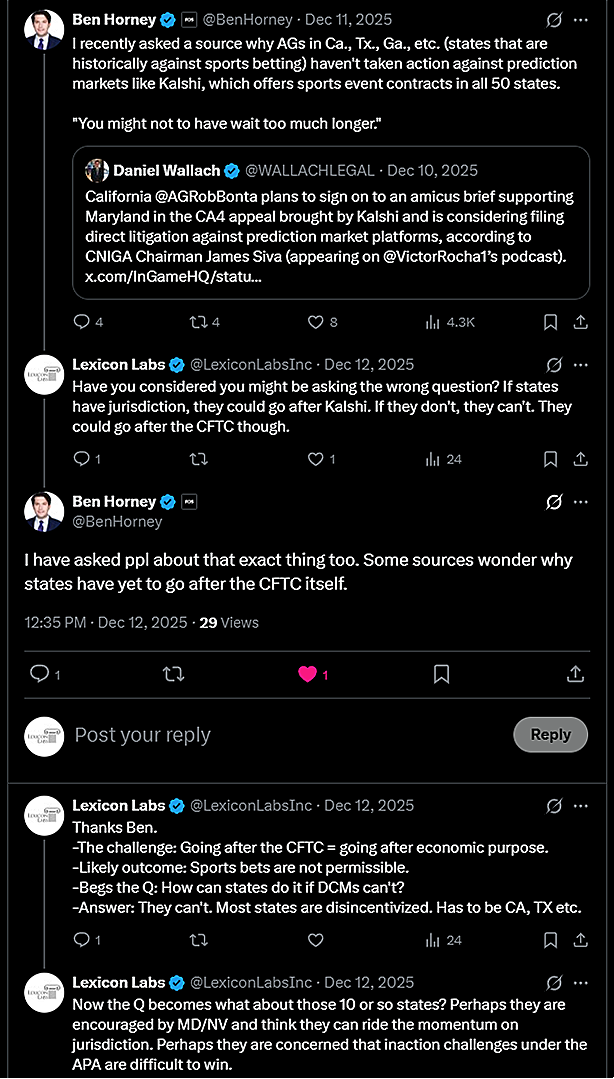

Consider our recent exchange with Ben Horney, the deals reporter at Front Office Sports:

So we return to the more plausible interpretation: FEC defines the boundary between federal and state jurisdiction. That boundary determines which direction legal outcomes will go and what consumers will ultimately see on the menu. Consider Coinbase’s most recent menu offering:

Coinbase’s new prediction markets and the litigation it immediately launched around it is the latest example that highlights the significance of FEC. It also makes one thing explicit: Their contracts only fall under federal oversight if the underlying events carry potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence. That threshold is the entire jurisdictional gateway. If an event lacks potential FEC, the CFTC has no authority, and without that authority these markets cannot operate on federally regulated rails in the first place.

Three Schools of Thought on FEC

1) The Invisible Line Theory

Super Bowl

NFL Conference Championships

NFL Divisional Round

NFL Wild Card Round

NFL Regular Season Games (Lions winning or losing their next game)

NFL Pre-season Games

…

Backyard catch with your kids

Somewhere between the Super Bowl and backyard football lies an “invisible line” where FEC disappears.

But where?

Take the Vikings-Giants Week 16 game for example. Both teams had already been eliminated, yet the market still traded $1.92 million worth of contracts on Polymarket. Did that game really have FEC? Is the Giants staying in the hunt for the top draft pick a potential FEC consequence? What about Jaxson Dart getting more reps? If not, why is this contract even listed on a federally regulated exchange? Mind you, we are not even having the gambling discussion yet. We are still in the jurisdictional determination stage.

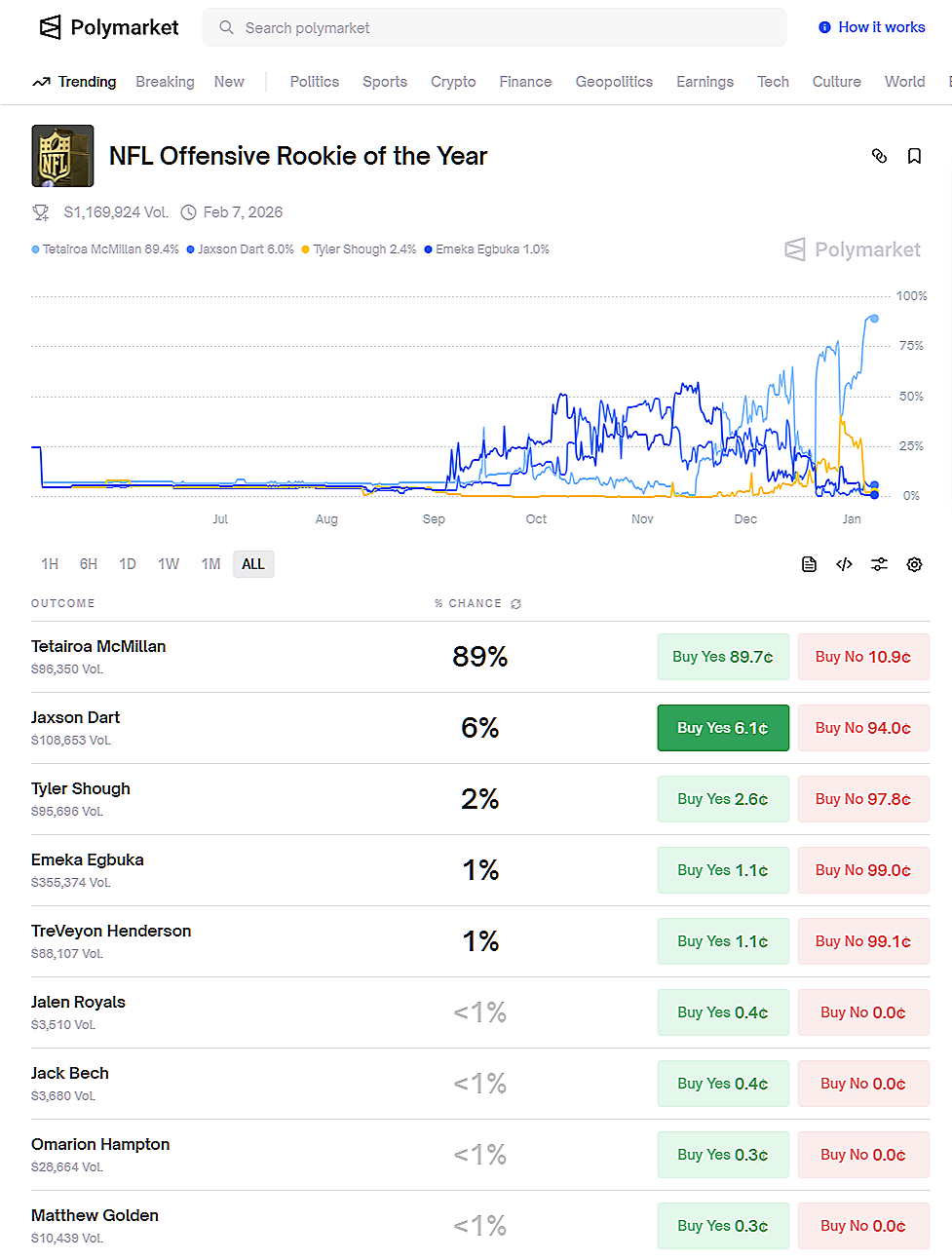

Does Jaxson Dart’s Rookie of the Year prop bet have FEC? What is the argument here? If he wins this award, it will have a quantifiable impact for the Giants and the hot dog stands around MetLife Stadium?

Let’s continue to explore. Does a meaningless player performance prop have FEC? Judge Chagares pressed the issue beautifully during oral argument in the Third Circuit (audio, PDF transcript):

What sports bets don’t qualify?

How granular does the economic impact need to be?

Kalshi had no choice but to admit that certain player props and bets (yes, they said bets) on little league games wouldn’t be swaps. It’s difficult to decide which issue is more annoying here–is it Kalshi openly admitting they are offering bets or is it the admission, under their own theory, that they are listing contracts on a federally regulated exchange where there is no federal jurisdiction in the first place?

Kalshi wants to have its cake and eat it too; it continues to list contracts that don’t belong, neither from a jurisdictional perspective (their concession, not ours), nor from an economic purpose perspective (this is the real issue).

The state tried to capitalize on the weakness of Kalshi’s argument:

On their point for limiting principles on their view, I don’t see any limiting principles. The ones that they’ve pointed to themselves are atextual. The idea that it has to have consequences out in the real world is true for literally everything.

Exactly. If everything has some economic ripple, then nothing provides a limiting principle.

Sports, by far, is the largest market, but the limiting principle problem extends across the board. Take weather contracts for example:

Snowfall at O’Hare? Sure, sounds consequential.

Snowfall at Madison & Wacker? Maybe, if you push really hard.

Snowfall at Madison & Wacker at 9:45 pm? Doesn’t seem plausible.

Snowfall in rural Decatur, IL at 9:45 pm on a street where nobody lives? Absurd.

The key insight here is that one can start with a contract associated with plausible commercial consequence and then ladder it down to the point where it becomes impossible to make the argument of financial, economic, or commercial consequence (the way Kalshi interprets the term).

This is exactly the type of line-drawing problem attorneys and judges love to hate. This is exactly how Judge Charages approached it.

It’s annoying to not be able to draw any meaningful lines, but if it’s that annoying, maybe the line is not meant to be drawn anywhere (insofar as contingent events are concerned), and the annoyance is a sign that there is a better statutory interpretation.

On top of the aforementioned annoyance, the CFTC staff is shrinking by the minute. Kalshi alone had 100 contracts in September 2024 and 1,000 in July 2025. On one occasion, 98% of Kalshi’s Sunday volume was sports related, with 92% of the volume on the NFL. This is just one prediction market, mind you. The invisible line theory collapses under its own weight. It forces the CFTC to become an FEC thermometer for tens of thousands of contracts. This is simply not a workable regulatory regime.

2) The “Anything Goes” Theory

If the invisible line can’t be drawn, then we’re left with a different problem entirely: The scope of FEC doesn’t narrow, it’s blown open. The question becomes not “where is the line?” but whether there is any line at all.

Once you reach that point, the pendulum naturally swings to the extreme:

If FEC has no limiting principle, does it eventually sweep in casino gaming itself?

That’s the real tension. If every event can be argued to have some potential economic consequence, then nothing stops the definition from expanding all the way into territory traditionally reserved for state‑regulated gaming.

Consider this hypothetical contract:

On the first roulette spin after midnight at Caesar’s Table #12 on date xx/xx/xxxx,

the ball will land on red.

This is a well-defined contingency. It’s verifiable. Under the “anything goes” interpretation, it could be listed on a federally regulated exchange. But, isn’t this really what any reasonable human would consider to be a game of chance, a classic bet? The possibilities are red or black (or the zeros), nothing else. All this time, the federal government had jurisdiction over casino games and we just missed it? Highly unlikely.

This is exactly what Nevada regulators fear: Prediction markets becoming prediction casinos. This was the title of a recent CDC Gaming article:

Nevada regulator fears prediction markets could expand into casino gaming and further threaten industry

Dreitzer, Nevada’s Gaming Control Board Chair, continued with more skepticism:

This is an existential issue for us. It may be sports betting, but it doesn’t stop there. There’s an opportunity from a technology standpoint to utilize the prediction outcomes to create slot machines and be the basis for RNGs (random number generators) for slot machines or for other types of casino gambling. We don’t want to end up with prediction casinos. (emphasis added)

“It may be sports betting, but it doesn’t stop there”… This line is the precise line-drawing problem translated into real-life consequence by the head of a gaming regulator. His point is certainly valid.

The Casino Association of New Jersey echoed the same concern (PDF amicus):

It is like a company opening an unauthorized casino just by calling its craps games “Dice Contracts” or its Blackjack tables “Card Contracts.”

This, too, would be absurd. Congress did not overhaul derivatives laws in 2000 to federalize roulette or table game outcomes. But the concern is not exactly unfounded, because if one can not find a limiting principle that works, the line could stretch all the way and subsume casino gaming.

The only potential counter is invoking the gaming prong under the Special Rule. However, that doesn’t work either. Using the gaming prong to solve a jurisdictional problem is backwards. You can’t say: Roulette is under the CFTC’s jurisdiction, it’s just impermissible.

That’s absurd. Roulette is not under the CFTC’s jurisdiction.

As is often the case, there is a third way. Once again, the ghost in the courtroom (podcast). It is the cleanest line that can be drawn and it is most likely what Congress had intended.

3) The Clean Line: Naturally Occurring vs. Artificial

This is where Nobel laureate Vernon Smith enters the chat. In his comment letter (PDF) to the CFTC, he offered the clearest limiting principle, and in our opinion, the one that should be used across the board in connection with any FEC inquiry:

Gambling involves the deliberate creation of artificial zero-sum opportunities to engage in risk taking decisions that redistribute existing resources.

Bingo! That’s the key.

Sports are naturally occurring competitions. They exist independent of gambling.

Weather is naturally occurring.

Elections are naturally occurring civic processes.

Casino games are artificially created for the sole purpose of gambling.

This simple distinction is elegant, intuitive and administrable.

Your backyard football game is naturally occurring. The Super Bowl is naturally occurring. Contracts on both fall under FEC. The CFTC can then use the gaming prong to filter out contracts that are contrary to public interest.

Roulette at Table #12 at Caesar’s? That is not naturally occurring. It’s engineered exclusively for wagering. Take these away and the casino ceases to exist. There is no CFTC jurisdiction here, the games belong to the states.1

Smith’s framework restores coherence and should be heeded.

Final thoughts.

We’ve landed on a logical, workable framework.

Naturally occurring events → Federal jurisdiction

All contracts on naturally occurring events fall under the CFTC’s exclusive jurisdiction.The gaming prong filters the permissible from the impermissible

If the CFTC enforced this properly, prediction markets would naturally converge toward essential, socially valuable contracts.Casino gaming remains entirely a state matter

Roulette, blackjack, craps, etc. do not occur naturally so they never enter the federal pipeline.

This is exactly where the U.S. was just a few years back. It made sense. Now we’re lost. It’s time for the judiciary to step in and provide the definitions and clarity that the CFTC seems to be waiting for.

Next up: A side-by-side comparison of excluded commodity and swap language in the CEA. Stay tuned.

That said, if you run a roulette game at home (with or without money), and somebody out there is placing bets on the game you are playing (on a federally regulated exchange or off-exchange), federal jurisdiction is invoked.