Kalshi v. CFTC - Round I

Part IX - Gaming vs. gambling

We like simple, short, memorable definitions. The definition of gambling should be:

Chance games, entertainment claims.

Thus, determining whether an activity is gambling involves a simple two-step process.

Step 1: Determine whether the activity is a game or a claim.

Step 2a: If the activity is a game, measure where the game lies on the skill vs. chance spectrum. If enough skill exists (however that boundary may be defined by the relevant law), the activity is not gambling.

Step 2b: If the activity is a claim, measure where the claim lies on the entertainment vs. purpose spectrum. If there exists sufficient valid economic purpose, the activity is not gambling.

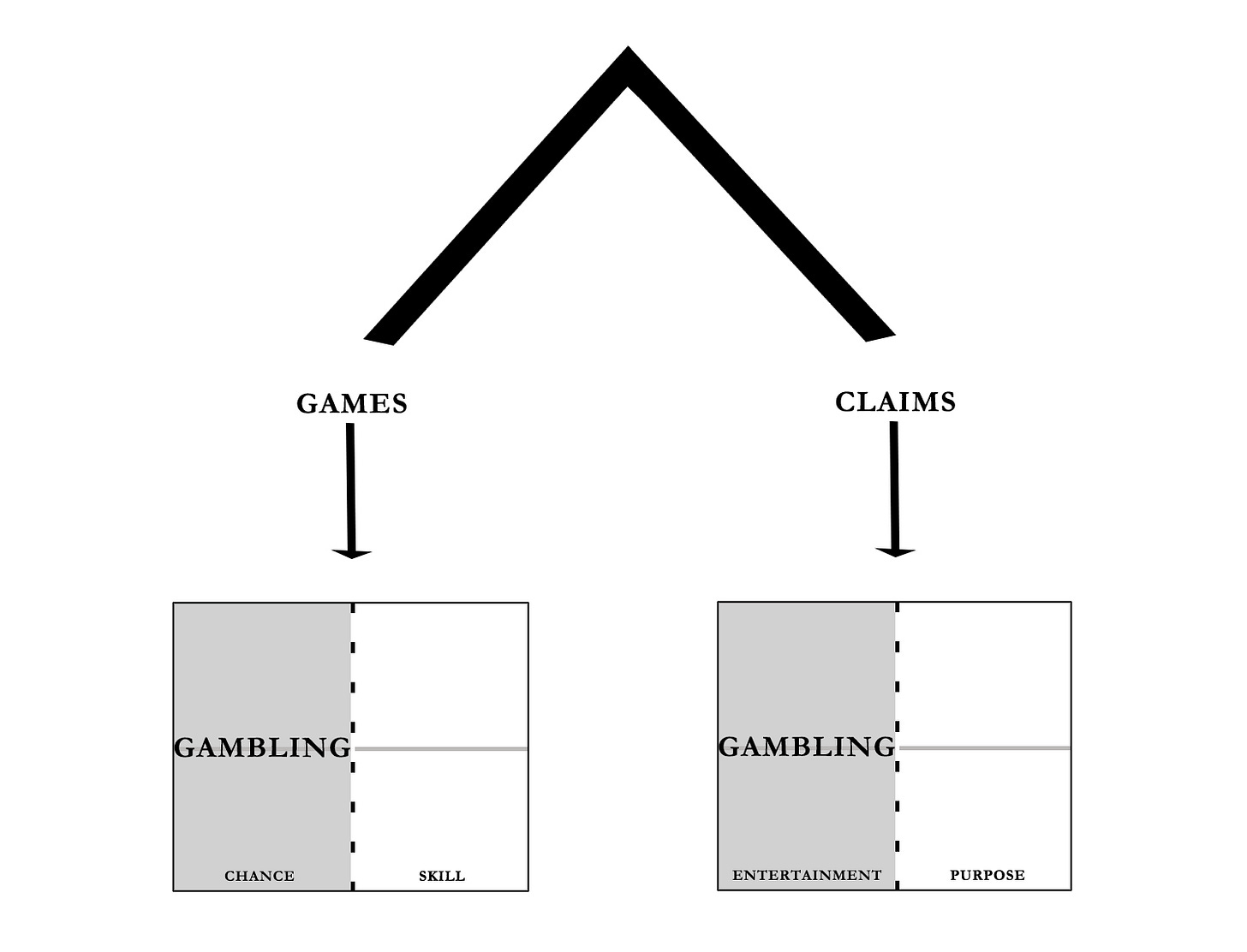

The following infographic depicts this two-step process:

Is the Activity a Game or a Claim?

Games

Under games, more skill means the characterization is moving away from gambling and once it is determined that the level of skill crosses the boundary, it ceases to be gambling. It is true that it is not always easy to agree on where that boundary lies; a complicating factor is that the states themselves apply different standards as to what constitutes “sufficient” skill. Still, this has been the test for games for many decades, if not centuries and some subjectivity is inevitable.

At one end of the spectrum, chess is considered a pure skill game, therefore not gambling. Roulette lies at the other end of the spectrum as a pure chance game, therefore it is gambling. These are clear edge cases where finding consensus is rather straightforward. Poker is arguably somewhere in the middle, and reasonable people can disagree whether it is a game of skill or a game of chance, which has resulted in never-ending arguments and a substantial body of case law.

Claims

A claim is a contract that is settled based on contingent events. An event contract fits that definition. If these contracts are considered to serve the public interest, they should be regulated by the Commission and they can only be traded on venues regulated by the Commission. If they don’t serve the public interest, the listing and trading of these contracts anywhere should be prohibited by the Commission.

So the question becomes, how much purpose is enough? Said differently, what is the level of economic purpose beyond which an event contract ceases to be gambling? At one end of the spectrum, event markets on interest rates may help parties manage many commercial risks. A sports bet lies on the opposite end of the spectrum and should easily be characterized as gambling, and box office futures lie somewhere in the middle. You may recall that box office futures were subject to a lengthy hearing back in 2010 (transcript, video). Despite strong opposition by the MPAA (now MPA), those contracts were voted to reach the market, 3-2, with then Chair Gary Gensler being the deciding vote. The Commission stated:

The contracts are intended to allow participants in the motion picture industry to manage the financial risks associated with the production and distribution of motion pictures.

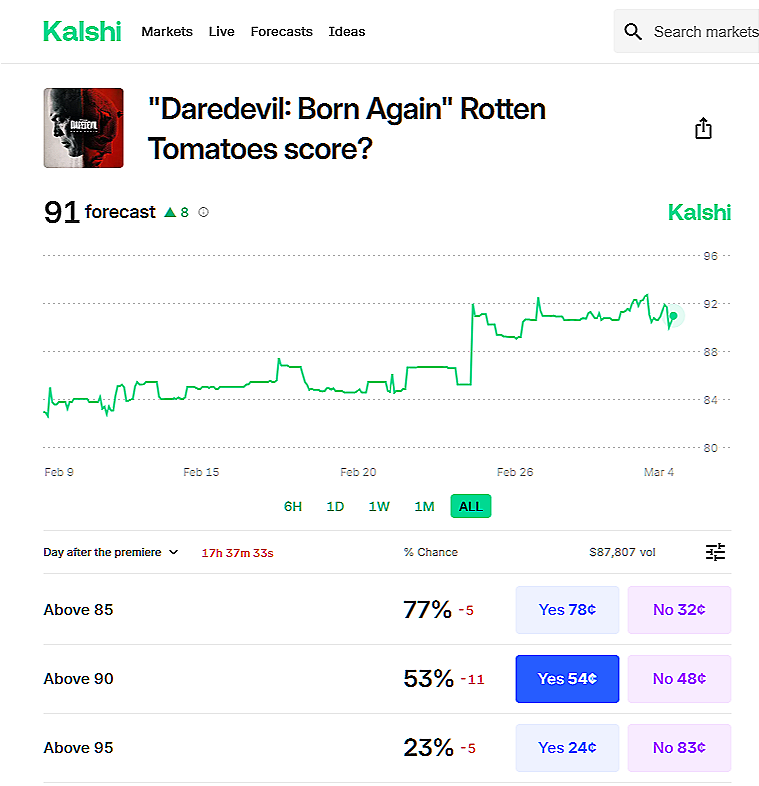

Congress eventually outlawed these contracts; a statutory ban exists today for box office futures as well as onion futures. Fear not though, you can still trade Rotten Tomato score predictions on Kalshi:

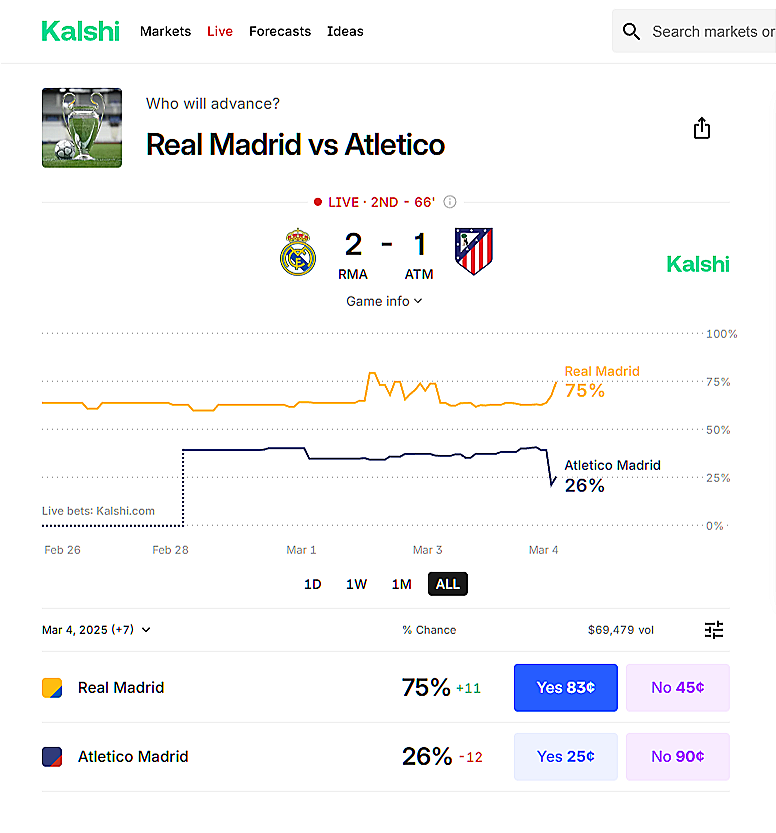

What economic purpose does this contract serve? Or, this one, for that matter:

This is outright gambling; it serves no economic purpose therefore it falls on the gambling side of the spectrum.

There was a time when the Economic Purpose Test meant something. This is what Kalshi v. CFTC should have been about but it turned into a tussle over definitions instead where both sides were wrong.

You know what else is interesting? The Economic Purpose Test was repealed in 2000, 10 years before the box office futures were debated. However, there really wasn’t much confusion as to whether that’s how the decision should be made. MPAA’s position was:

The MPAA has also said that futures contracts based on box office receipts have no economic purpose.

This was the counter position:

Weakest among the risk bearers include the financial investor who places capital in a multi-year film fund, the small theater owner who commits screens to major studios based solely on representations of those studios, and the production company that has little control over the marketing and distribution of its film. We submit that these commercial interests, combined with non-MPAA studios, represent a large enough and significant hedge community to meet the requirements for economic purpose under the Commodity Exchange Act.

The point is not which side you are on. Reasonable minds can disagree on whether or not these contracts serve an economic purpose. Everybody agreed the Economic Purpose Test is how the dispute should be resolved. It is true that the Dodd-Frank Act was signed into law in July 2010, but the Economic Purpose Test wasn’t on the books even prior to that and still isn’t. However, as the excerpts from the box office futures hearing demonstrated, it still governed the decision making around innovative financial contracts.

This will be the tarnished legacy of Kalshi v. CFTC. It took the consensus dispute resolution mechanism away without replacing it. Largely, and unfortunately, it was the CFTC’s own making.