Poker, Tetris, and Taylor Swift (Chiefs) Are Out. Seychelles, Big Beautiful Bill, and Taylor Swift (Beyonce) Are In

Did Congress really intend this outcome when they passed Dodd-Frank?

One of the best ways to test a statutory interpretation is to follow it to its logical conclusion and ask: Does the result make sense? In Kalshi v. CFTC, we will never know how the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit would have ruled–the CFTC dropped the case earlier this month. We do know how the lower court ruled though, and for now, that ruling defines the law.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at the current landscape. We can examine:

What Kalshi is actually offering its customers (Dustin Gouker at Event Horizon keeps a close watch on these contracts).

The CFTC’s proposed rules on event contracts–not likely to move forward in its current form, but still revealing in its intent.

If we blend all these ingredients and add a touch of historical context, what we end up with is… well, revealing. Read on, and decide for yourself whether the status quo makes sense.

The Roots of the Regulation: A Crisis and its Aftermath

The 2007-2009 financial crisis was one of the deepest and also the longest recessions the U.S. had ever seen. From peak to trough, GDP shrank by 4.3%, the unemployment rate more than doubled (hitting 9,9% in 2009), and revered financial institutions collapsed seemingly overnight. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, Merrill Lynch, Bear Sterns and Washington Mutual avoided that fate but only due to eleventh-hour rescues. Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big Too Fail beautifully captured the zeitgeist.

At the heart of this turmoil was excessive risk-taking. As the government put it:

In the fall of 2008, a financial crisis of a scale and severity not seen in generations left millions of Americans unemployed and resulted in trillions in lost wealth. Our broken financial regulatory system was a principal cause of that crisis. It was fragmented, antiquated, and allowed large parts of the financial system to operate with little or no oversight. And it allowed some irresponsible lenders to use hidden fees and fine print to take advantage of consumers.

To make sure that a crisis like this never happens again, President Obama signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act into law. The most far reaching Wall Street reform in history, Dodd-Frank will prevent the excessive risk-taking that led to the financial crisis. The law also provides common-sense protections for American families, creating new consumer watchdog to prevent mortgage companies and pay-day lenders from exploiting consumers. These new rules will build a safer, more stable financial system—one that provides a robust foundation for lasting economic growth and job creation. (emphasis added)

To prevent another catastrophe, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, the most sweeping reform in Wall Street History at more than 2,300 pages. The law’s purpose was clear: reign in excessive speculation, create consumer protections and ensure that financial markets serve an actual economic function.

Event markets, a relatively new financial instrument at the time, weren’t immune from scrutiny. The CFTC was grappling with an essential question:

Event markets are rapidly evolving, and growing, presenting a host of difficult policy and legal questions including: What public purpose is served in the oversight of these markets and what differentiates these markets from pure gambling outside the CFTC’s jurisdiction?

The gambling concern wasn’t theoretical. At the oral argument stage in Kalshi v. CFTC, the agency reiterated the same stance (but ultimately took its argument elsewhere):

To build and maintain a thriving derivatives industry that is distinct from the gambling business has been the work of 175 years, and it's important.

Drawing the Red Line: What Qualifies as “Gaming”?

Congress wasn’t naive to the risks that unchecked event markets might pose. While it did not explicitly prohibit certain contracts in the statute, the special rule in the Commodity Exchange Act Section 5(c) outlines specific categories–including terrorism, assassination, war and unlawful activity–which the CFTC is authorized to evaluate. If the Commission determines that a contract falls within one of these categories and lacks economic purpose, it has the authority to reject it.

Then there’s gaming, and it requires its own interpretation. Kalshi argued that “gaming” simply means “games,” yet they never addressed the obvious canon of construction issue: If Congress had truly meant games (the noun), why didn’t it just say so? Terrorism, assassination, and war were all nouns, it would have been entirely natural to include “games” in the same list.

Kalshi’s interpretation was problematic, but at least it aligned with some dictionary definitions of “gaming.” The CFTC’s interpretation, however, was even more problematic. They argued that “gaming” encompasses not just games but contests–an expansive definition (relative to Kalshi’s) that could include elections and even awards like the Oscars. Kalshi hammered this interpretation (rightfully so), pointing out that “gaming” could reasonably mean just games (their stance) or possibly gambling (our interpretation), which would imply that all contingent event contracts might be subject to review. Effectively, Kalshi conceded that the Court of Appeals’ reasoning was sound (the same as ours)–but they caught a lucky break, because the CFTC wasn’t arguing along those lines! That allowed Kalshi to paint the CFTC not as a neutral regulator and genuine truth seeker pursuing the correct statutory interpretation, but as a politically motivated opponent. Kalshi argued that the CFTC conveniently chose a middle-ground definition only because it was a means to an end, serving its goal of denying election contracts.

They had a point, and the argument resonated with the lower court, which was unwilling to consider that neither Kalshi’s nor the CFTC’s interpretation was necessarily the best one. The Court of Appeals signaled it might explore this possibility–but by dropping the case, the CFTC ensured that opportunity never materialized.

Where Does That Leave Us Now?

Based on the court ruling and other positions taken along the way, here’s a sample list of what’s in and what’s out:

Banned as “Gaming”:

Who will win the World Series of Poker?

Will an Oklahoma prodigy clear 2,000 lines in Tetris?

Will Taylor Swift attend a Kansas City Chiefs game?

Allowed as financial instruments that supposedly serve the public interest:

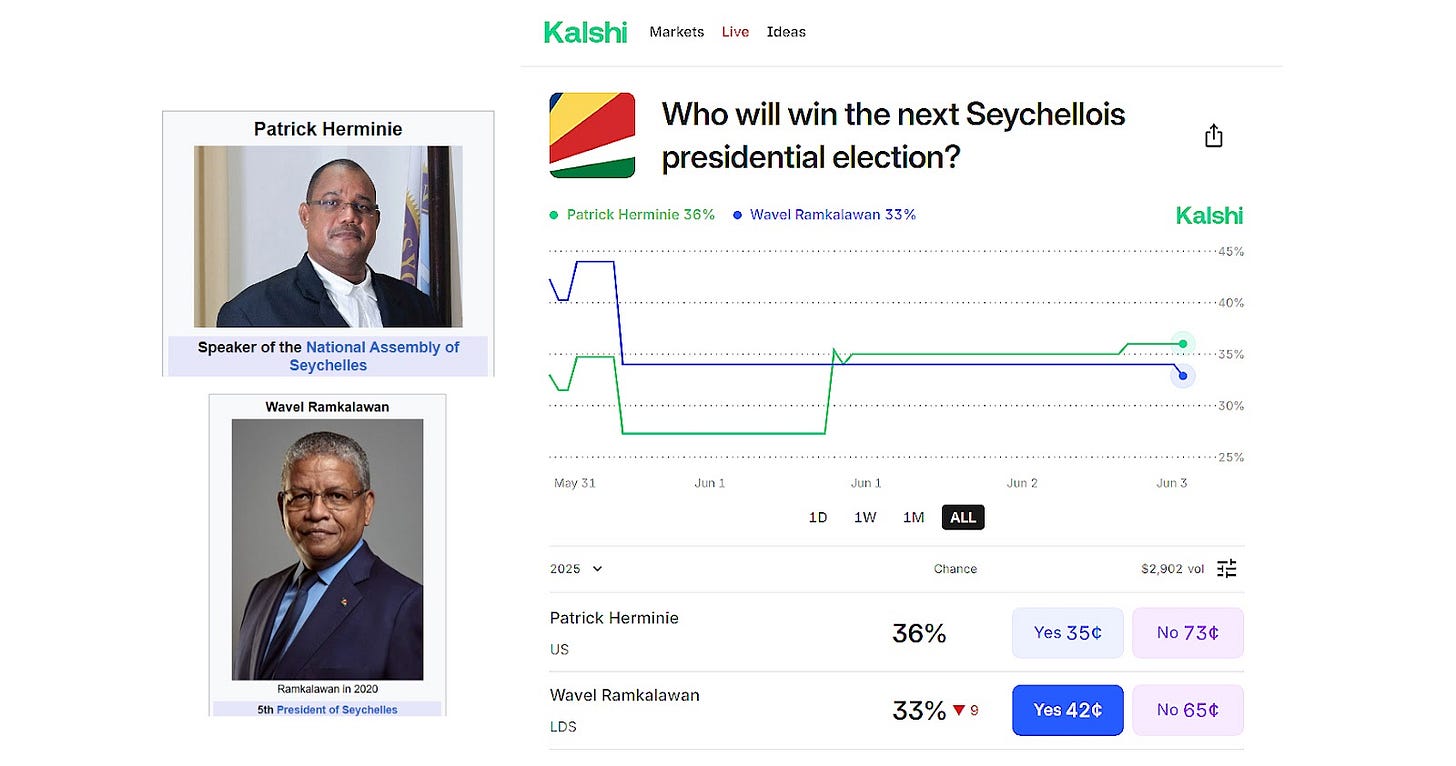

Who will win the next Seychellois presidential election?

Will the Big Beautiful Bill clear 20,000 lines? (ok, we made this one up, but hey, Kalshi–maybe you should consider it.)

Will Taylor Swift attend a Beyonce concert?

Do you see where this takes a turn? What started as a serious analysis of financial regulation suddenly feels like satire.

And yet, these examples aren’t random. The poker contract is one that was mentioned in the district court opinion as a potential gaming contract. The Tetris example? Straight from the CFTC’s oral argument before the Court of Appeals. The Taylor Swift Chief’s game attendance contract? It’s purely hypothetical (as far as we’re aware)–but it serves a crucial purpose. Ex-Commissioner Mersinger introduced it in her dissent against the CFTC’s proposed rulemaking on event contracts to illustrate what kind of contracts can be caught in the CFTC’s net if its proposed definition is adopted (and which ones won’t, see below).

On the flip side, the Seychelles election contract is currently being offered by Kalshi:

As mentioned, the length of the Big Beautiful Bill contract is one we made up, but look at this collection of available contracts, and it becomes rather obvious that it wouldn’t look out of place.

The Beyonce concert contract? This was another hypothetical example Ex-Commissioner Mersinger so cleverly constructed. Put side by side with the Taylor Swift attending the Chiefs game contract, it perfectly illustrated how the CFTC’s interpretation of “gaming” creates bizarre contradictions: The same contract–Swift attending an event–becomes unacceptable when it’s a football game but perfectly fine when it’s a concert. This contrast lays bare how subjective the CFTC’s application of the rule truly is.

Does This Make Sense?

Put your hand on your heart and answer us this: Do you truly believe this is what Congress envisioned when drafting financial regulations post-recession? Because, like it or not, this is the status quo.

One court has effectively endorsed this reality. The Court of Appeals saw the flaws and began to push back–until the CFTC shut the case down before that argument could gain any traction. The result? A regulatory landscape where some contracts are gaming and others are financial instruments, based not on their public utility, but based on their proximity to “games,” leading to further ambiguity and a distinction that makes no sense. To call this a failure by the CFTC would be a massive understatement–one whose consequences may not become obvious for years unless meaningful intervention takes place.

Alas, if you’re inclined to place a wager (and let’s be honest, we call it that because no one is seriously going to argue that Seychelles elections create significant risk for U.S. businesses) on elections in a country you likely cannot locate on a map–well, as of today, nothing stands in your way.