Kalshi v. CFTC - Round I

Part XI (Finale) - This round goes to Kalshi, but it may not be over just yet

Kalshi secured victory in Round I, and many people, us included, have been waiting for how Round II (the appeal), was going to play out. There is nothing to wait for anymore now that the CFTC decided to drop the appeal.

Dustin Gouker over at The Closing Line was not surprised:

In reality, it was shocking this case was still going on at all. Oral arguments happened earlier this year in the appeal, and there had been a filing by the CFTC and a response by Kalshi after Nevada had sent a cease-and-desist letter to Kalshi for allegedly offering election betting and sports betting illegally in the state. The election betting case had started under the Biden administration; meanwhile, President Donald Trump had hailed prediction markets and election betting in the wake of his November victory. The case had stood in stark contrast to the permissive and hands-off approach the CFTC has taken on the expanding sports betting offering from Kalshi and Crypto.com.

Tarek Mansour, Kalshi’s CEO was obviously relieved:

So, even though we will never know how the Court of Appeals would have ruled, we feel this story is far from over. So, let’s finish up Round I. We gave you 10 posts on this case already but if you are looking for a quick recap, you can start with this post.

Gambling Games - A Spectrum

Is poker gambling?

This was the question that Lawrence DiCristina was facing. He ran poker games in the back of a warehouse and he was caught. If poker is gambling, there would be serious repercussions for him, including potential jail time. If it isn’t, he’d be a free man. This law review piece recounted the story.

You may already have an opinion on this. Maybe poker is just another gambling game for you. Or maybe, you are in the poker-is-not-gambling camp. Either way, you have likely formed, knowingly or otherwise, an opinion as to how much skill is involved. This is so, because when it comes to games, whether a game is gambling or not turns on whether the game in question is a game of skill or game of chance. If the former, it is not gambling. If the latter, it is.

Consider this visual (Spoiler alert: A version of this image will be the cover design of one of our upcoming books):

The path is the chance-skill spectrum that delineates gambling. Every possible game resides somewhere on that path. The white arched structure is the gate that is crossed when a game is considered to involve sufficient skill, and therefore is not considered gambling; hence the green floor. If a game does not involve enough skill to advance through that gate, then the game is considered gambling; hence the red floor.

The question you might then ask is, where exactly on that spectrum is the boundary that separates games of chance from games of skill? How much skill is considered enough? States have different views on this, but more than half apply the predominance test, where courts consider whether skill or chance is more likely to influence the outcome of a contest. The same law review piece explains what that means:

In this context, scholars state that “predominates” refers to a 51% benchmark such that if chance plays a 51% or greater role in the game, chance predominates over skill.

Some games are very easy for one to know where on the spectrum it would fall. Chess is 100% skill so it sits comfortably at the end of the spectrum, well beyond the gate, in the green. Roulette is equally easy, it resides on the opposite end of the spectrum; it doesn’t even come close to being a game of skill. It’s pure chance and therefore sits solidly on the red path, at the farthest point from the gate.

Spectrums like these are also relevant for educational outcomes or job settings. As most teachers and supervisors would attest, the bookends are generally the easy cases. The top performers comfortably pass the class or get the promotion and the ones that don’t perform at all fail or are denied the promotion (or worse, get fired).

Borderline cases are often the toughest. As a teacher, those were always the ones that made me think. In the workplace, heated conversations were mostly about the ones that had mixed feedback. In both settings, the Pareto principle applied, 80% of the time was spent on 20% of the cases.

Poker is that problematic case. There is just enough skill that makes you think, but it is not clear whether there is enough of it.

This post is not a write-up on DiCristina (maybe another day), so we’ll spare you some details. Let’s just say that the District Court decided there is enough skill (therefore, poker is not gambling). Here is the opinion. Here is a summary by K&L Gates.

On appeal though, the Second Circuit reversed. DiCristina petitioned the Supreme Court and there was some engagement from the community in the form of amicus briefs. The Supreme Court declined to hear the case. DiCristina avoided jail time and was sentenced to one year of unsupervised probation.

Gambling on Events - ALSO A Spectrum

Are election contracts gambling?

This is the question Kalshi faced in Kalshi v. CFTC. (Round I). Ultimately, this entire series was about how that question could have been resolved.

This is where it gets very interesting. From our perspective, this is simply another spectrum question and you resolve it exactly the same way. We will save you some real estate and won’t reproduce the image above, but you can literally use the same image.

In this instance, of course, it’s not about skill vs. chance but rather purpose vs. entertainment. Remember, the Grain Futures Act of 1923 (the precursor to the Commodity Exchange Act) was all about making sure that futures markets don’t turn into gambling platforms.

The Commodity Exchange Act of 1936 brought some needed structure to the market. Then, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974 formalized the idea of keeping gambling at bay by introducing the economic purpose test. Under the economic purpose test, any futures contract simply wouldn’t do, it needs to be used in commercial circles as a hedging device or as a basis for pricing. That white arch structure pictured above, in the context of futures contracts, symbolizes the economic purpose test. The relevant skill test (e.g. the predominance test) is to the gaming regulator as the economic purpose test is to the CFTC.

The Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 (“CFMA”) expanded the universe of commodities, bringing virtually anything and everything under the commodity umbrella, and therefore, futures contracts on those commodities under the CFTC’s purview (the CFTC does not regulate commodities, it regulates commodity futures).

Remember what the red and green pathway symbolizes in the gaming context: Every possible game resides somewhere on that path, with games clearing the skill bar sitting on the green portion, because they are not gambling. A very similar interpretation applies in the context of futures contracts: Every possible futures contract, including event contracts resides somewhere on that path, with contracts clearing the economic purpose bar sitting on the green portion, because they are not gambling. Furthermore, the passage of CFMA meant the CFTC’s role was going to increase because as the definition of commodity expanded, so did the universe of contracts falling under the CFTC’s purview. The event markets hadn’t really come into existence yet, but the stage was being set for the CFTC to expand its reach.

A literal reader of the CFMA might have concluded that Congress, while expanding the universe of potential futures contracts with one hand, took away the only tool the CFTC had to opine on these contracts with the other. It’s akin to the number of students in the classroom increasing, but the authority to grade the students' work being taken away from the teacher.

That conclusion, intuitively, was challenging to digest. As Peter Parker learned early on, with great power comes great responsibility. Of course, responsibilities require the necessary tools. If anything, the CFTC should have been armed with more tools, not less.

Early on, for all intents and purposes, the CFTC ignored the fact that the economic purpose test was repealed by the CFMA because not having that tool in its arsenal did not make much sense. In the Commission’s view, the economic purpose test was alive and well. Indeed, when deciding the fate of box office futures in 2010, ten years after the passage of CFMA, the CFTC, by and large, continued to rely on the economic purpose test.

As a result of the 2008 economic recession, Dodd-Frank was born and this is how the CFTC described it:

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act) enhanced the CFTC’s regulatory authority to oversee the more than $400 trillion swaps market. (emphasis added)

Dodd-Frank was a big deal, though reading the Kalshi transcript, one would not necessarily conclude that. It was a reform, not an amendment to “streamline the process.” Kalshi minimized the significance of Dodd-Frank during litigation, and the CFTC, for unknown reasons, chose to go along with it, ultimately burying the economic purpose test in the process.

We don’t believe Kalshi itself expected that the CFTC would abandon its North Star so easily. It is pretty clear that Kalshi anticipated a competitive bout along those lines. Rightfully so, because, let’s be honest, how else can these product decisions be made?

Poker creates disagreements in the gaming space because it is a mixed bag of chance and skill. Election contracts create disagreements in the gambling space because it is a mixed bag of some price discovery and very limited hedging.

Ultimately, the question was this:

Should one be able to risk money on a presidential candidate winning the election?

A question that can be answered only with the aid of the economic purpose test. A little more than a decade ago, that’s exactly what happened.

NADEX Goes Nowhere

Back in 2012, the CFTC answered the question posed above largely with reference to the economic purpose test, notwithstanding its repeal 12 years prior. Here is a key excerpt from that decision:

WHEREAS, the legislative history of CEA Section 5c(c)(5)(C) indicates Congress's intent to restore, for the purposes of that provision, the economic purpose test that was used by the Commission to determine whether a contract was contrary to the public interest pursuant to CEA Section 5(g) prior to its deletion by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000;

We fully agree. The Commission also reminded everyone what economic purpose meant:

WHEREAS, the restored economic purpose test calls for an evaluation of an event contract's utility for hedging and price basing purposes;

How did the election contracts fare in that regard? According to the Commission, it didn’t do much on the risk management side:

WHEREAS, the unpredictability of the specific economic consequences of an election means that the Political Event Contracts cannot reasonably be expected to be used for hedging purposes;

In fact, the Commission didn’t even think it does much on the price basing side:

WHEREAS, there is no situation in which the Political Event Contracts' prices could form the basis for the pricing of a commercial transaction involving a physical commodity, financial asset or service, which demonstrates that the Political Event Contracts have no price basing utility;

The Commission didn’t want to leave any stones unturned so it commented on integrity as well. First, the setup:

WHEREAS, the Commission has the discretion to consider other factors in addition to the economic purpose test in determining whether an event contract is contrary to the public interest;

Then the punch:

WHEREAS, the Political Event Contracts can potentially be used in ways that would have an adverse effect on the integrity of elections, for example by creating monetary incentives to vote for particular candidates even when such a vote may be contrary to the voter's political views of such candidates;

Finally, the knock-out:

The Commission FINDS that the Political Event Contracts involve gaming as contemplated by CEA Section 5c( c )(5)(C)(i)(V) and Commission Regulation 40.11 (a)(l);

The Commission FURTHER FINDS that the Political Event Contracts are contrary to the public interest as contemplated by CEA Section 5c(c)(5)(C);

Therefore: IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that, pursuant to CEA Section Sc( c )(5)(C)(ii) and Commission Regulation 40.11(a)(1), the Political Event Contracts shall not be listed or made available for clearing or trading on the Exchange.

Kalshi is Delivered a Gift From The Heavens

Several years back, Nadex had put together a pretty hefty dossier about election markets. The price discovery function of election markets has always been its stronger argument. The hedging? Not so much. In the end, the Commission did not budge on it either.

With Kalshi, effectively, the same contract was in front of the Commission again, only by a different exchange. Would this time be any different?

Certainly, when the CFTC denied Kalshi, the order still featured economic purpose heavily. It included very similar language to the Nadex decision from 2012:

WHEREAS, the legislative history of CEA section 5c(c)(5)(C) indicates Congressional intent for the Commission to consider, among other things, in its evaluation of whether a contract is contrary to the public interest for purposes of that provision, a form of the “economic purpose test” that was applied to determine whether a contract was contrary to the public interest under former CEA section 5(g) prior to its deletion by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 (“CFMA”).

Notably, this language was a bit softer than the language the Commission used back in 2012. “Congress's Intent to restore” became “Congressional intent for the Commission to consider, among other things…” The economic purpose test turned into “a form of the ‘economic purpose test’, with the word form softening the stance and the economic purpose test being wrapped into quotation marks. In hindsight, perhaps these were signs that the Commission was not completely comfortable with the idea of using the economic purpose test. Still, the order dedicated about four pages to hedging and price basing and used those arguments before it presented the integrity arguments.

Kalshi runs prediction markets. If they ran a prediction market at that point in time regarding what the CFTC’s legal strategy would be, we feel the economic purpose test would still be the leading candidate.

Instead, the CFTC did the inexplicable: It removed the arched gate altogether.

Had the CFTC followed in the footsteps of the 2012 Commission, it would have been a win-win for them. No matter where the decision would have landed, the CFTC, and society at large for that matter, would have been in a much better spot than they are now. In Part V, we said:

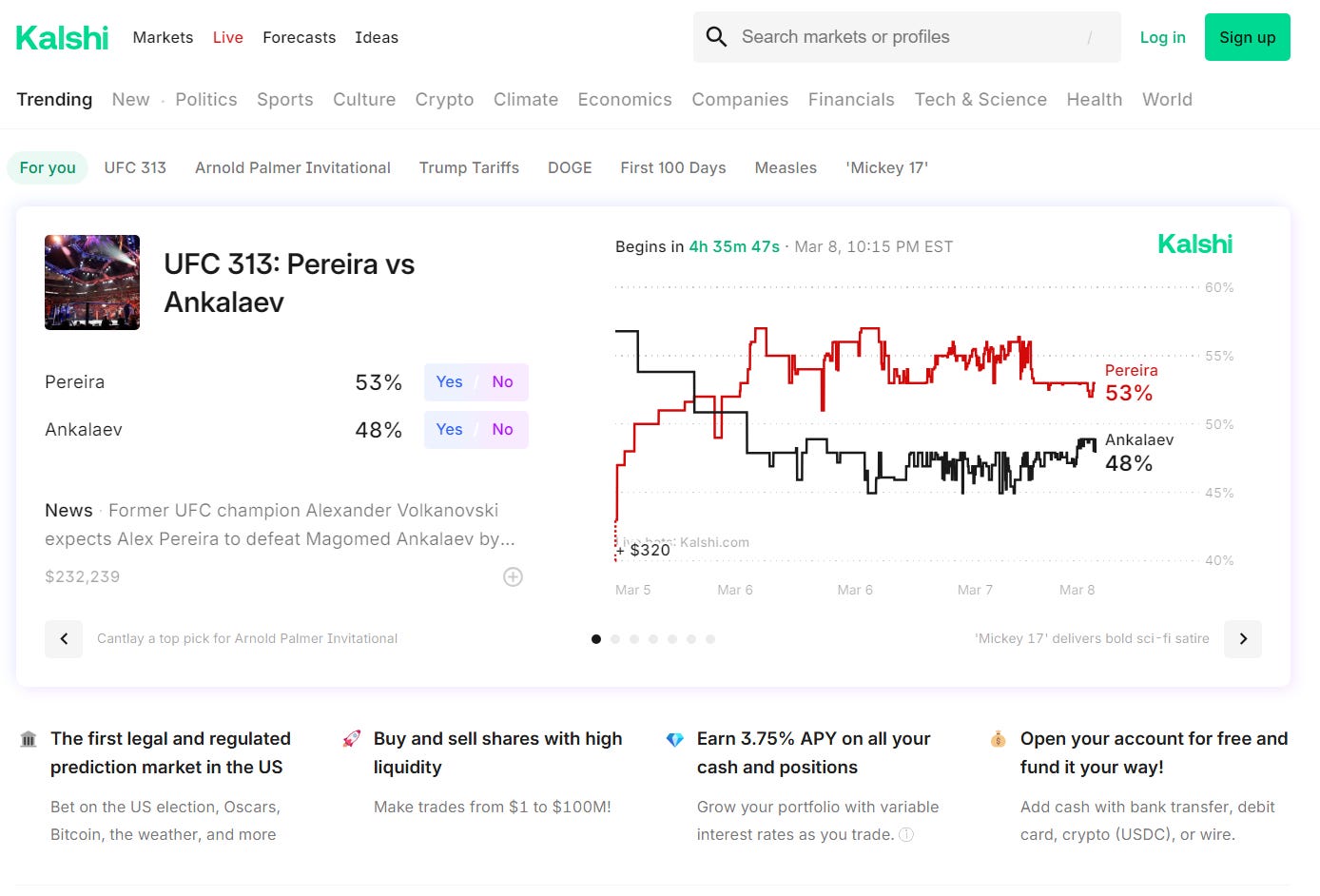

Had the CFTC argued that it has the authority to review, and potentially ban, any event contract, it might have still lost the battle (on economic purpose), but it would have won the war. It would have preserved its right to go after the event contracts that have much less economic purpose than the election contracts. Now it’s helpless as Kalshi lures people in by encouraging them to “bet on the US election, Oscars, Bitcoin, the weather, and more.”

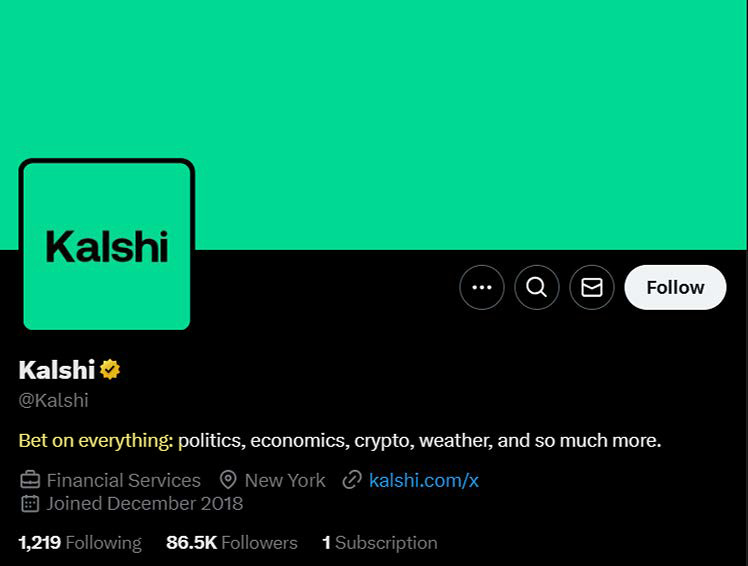

(NB: the website actually says “trade” now, but it used to say “bet.” The same for Kalshi’s X page. Luckily, we took snapshots of both before Kalshi managed to change them; the webpage snapshot below was taken on March 8, 2025, and the X snapshot below was taken on January 8, 2025 - the yellow highlight is ours)

The Commission, however, didn’t go down that path. Kalshi found a way to bait the CFTC into turning the case into an argument over definitions and it worked. As a result, the economic purpose test became an afterthought. Ultimately, with the integrity argument in tow, the CFTC’s unwillingness to become an “election cop” took center stage.

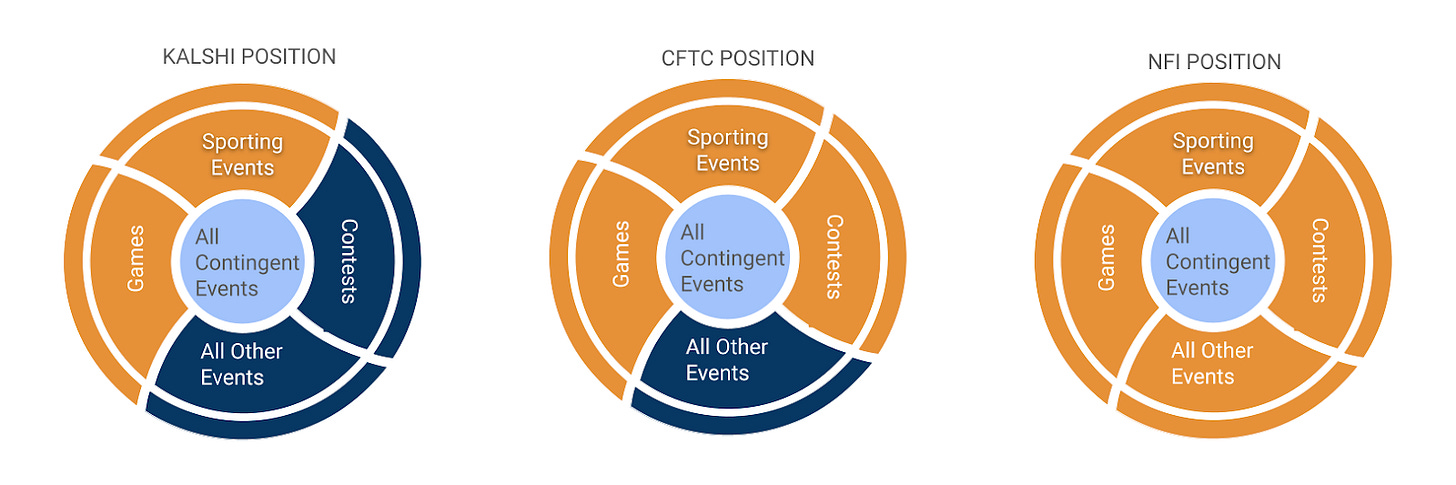

We are fond of this picture that we produced in Part III of our series:

The principled argument, which, in our opinion, also happened to be the CFTC’s best shot to win consisted of three steps we laid out in the same post:

Step 1 - Acknowledging that when Congress used the word gaming, it actually meant gambling;

Step 2 - Recognizing that all contingent events are in play, and therefore all event contracts fall under the CFTC’s purview (even if that meant more work for the Commission); and

Step 3 - Not sacrificing its North Star and doubling down on the economic purpose test, and confidently arguing that, while repealed, the economic purpose test should still be the guiding principle.

Instead, the CFTC turned it into a definitional fight, and wound up with the following:

Step 1 - Acknowledging that when Congress used the word gaming, it actually meant gambling (so far so good); but

Step 2 - Contradicting that position by refusing that all contingent events are in play, and thus restricting the universe of contracts it actually has the discretion to review; and

Step 3 - Allowing the Court bailing Kalshi out because restricting the universe of contracts in Step 2 led to the (reasonable) conclusion that if the CFTC believes that it does not have the authority to review a contract (if it so wishes) in the first place, economic purpose doesn’t even need to be considered.

If Arguments Were Basketball Players…

Back in 2012, the economic purpose test was clearly the star of the team, the go-to option. The Kalshi order that was handed down signaled that its workload may be reduced some and its minutes may be managed, but the economic purpose test was still the go-to option. When litigation commenced, however, it wasn’t even a role player anymore, let alone being the star player; effectively the economic purpose test was benched for undisclosed reasons.

When a team benches its best player, it doesn’t give itself the best shot to win. That’s what happened to the CFTC by ignoring the economic purpose test.

Outlook

Where do we go from here? It looks like the election markets are here to stay, for now. That said, we wouldn’t put much confidence into the longevity of these markets. Notwithstanding the dropped appeal, there were still some signs during oral argument (at the appeals stage) that the economic purpose test is alive and well.

We believe that the issue will be re-litigated eventually, it’s too important. When that happens, we expect that the economic purpose test will be back at center stage. The true fate of event markets will be decided then.

If you are Kalshi, you might want to run a prediction market on that. After all, unlike many of the markets that are available to traders on your platform today, that contract may have just enough purpose to get you over the hump when it comes to economic purpose.