Kalshi’s Gambit: The Bet That Could Break Sports Gambling

Prediction markets are testing the limits—and the law. Will all the dominoes fall?

Last week, we dismantled the notion that the “sports-is-a-commodity” theory (or, alternatively, the “sports-event-contracts-are-swaps” theory) was some post hoc invention by Kalshi–an argument that came out of left field. Instead, we argued that this idea has been lurking in the background all along.

Our position, in short:

Did the Supreme Court know that sports event contracts might be a type of commodity futures? Yes.

Did Congress authorize sports gambling with Dodd-Frank? No.

These two ideas are on a collision course–likely in D.C.; whether in the Supreme Court building, the halls of Congress, or both remains to be seen. In anticipation of that, today, we’re continuing to build the record.

The Broader Strokes

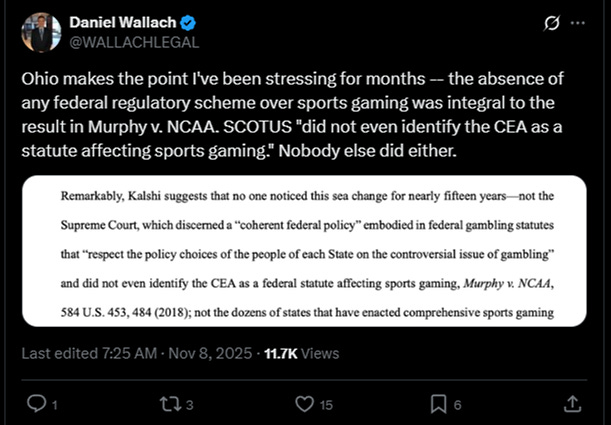

Let’s zoom out. There’s a growing theme in legal circles that dismisses the idea of federal preemption in the context of sports event contracts as laughable, because, supposedly, it wasn’t raised before. Consider this post by Wallach:

(An earlier version of this post actually finished with “None of the parties or amici did either.”)

Wallach doesn’t need to agree with us that the CEA preempts. But his claim that nobody raised these issues? That’s simply not true. How do we know? Because we raised them–as amici in Murphy v. NCAA (PDF).

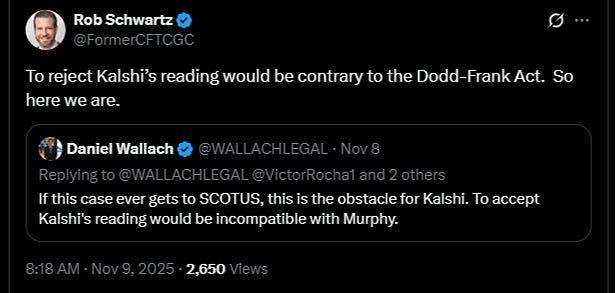

Now consider this exchange between Wallach and Rob Schwartz.

Schwartz, now a partner at Morgan Lewis, was the former General Counsel of the CFTC. He represented the agency in the Kalshi case, which we covered extensively (start here).

This brief exchange foreshadows a deeper tension that could surface in a Supreme Court showdown. But the real tension isn’t legal–it’s commercial. Backdooring sports gambling is precisely what Congress wanted to prevent. The absence of legal ambiguity only sharpens the business risk.

Three Questions Worth Exploring:

Who Will The Parties Be?

Will this issue ever reach the Supreme Court? Most likely. Will Kalshi–or another DCM–be a party to the suit? One commenter thinks so (his pick is Maryland). We’re not so sure.

If not Kalshi, then who? It could be the CFTC itself, targeted in an APA action for its inaction on sports event contracts. We discussed this possibility in our New Jersey amicus brief (PDF). No such challenge is on the horizon just yet–likely because it could destabilize state-regulated sports gambling, and few states are incentivized to go there. Eventually, though, someone will.

We love sports analogies so let’s take a look at one! There is a cliché in the NBA: A play-off series doesn’t start until someone loses on their home court. Taken literally, it’s false as some series end without that ever happening. But the point is: Things really don’t get interesting until someone breaks serve by winning on the opponent’s home court.

We suspect the judiciary may end up having its own version of that cliché. By our count, there are roughly 20 sports event contract cases in the pipeline (and likely more on the horizon). But real litigation won’t start until there’s an APA challenge. We believe that’s the case that will crack open the SCOTUS front doors.

Will Kalshi Lose?

If Kalshi is a party to the suit, they absolutely could lose. All it takes is a finding that there’s no federal jurisdiction over sports event contracts. At that point, Kalshi would either have to shut down their sports event contract operations (which is a majority of its business), or pivot to state licensing.

The more interesting scenario is an APA challenge–where Kalshi might lose without even being a party to the suit. That outcome would likely hinge on two concurrent findings:

Sports event contracts are swaps and/or sports is a commodity; and

Sports event contracts are contrary to public interest.

That doesn’t exactly seem farfetched, does it?

Are Sports Event Contracts Contrary to Public Interest?

We believe they are. There are two paths to consider. The simplest path to that conclusion is through the ‘gaming’ prong in the Special Rule–which Kalshi has already agreed includes sporting events. It’s almost poetic: Combine one argument Kalshi made in 2025 with another from 20241, and the result is the company’s own undoing.

The CFTC’s own implementing regulations support this view, but to this point, that somehow hasn’t carried enough weight. Former Commissioner Quintenz believed the regulations were invalid to begin with, so if they get more attention, that issue may be back on the table.

Perhaps one of the strongest arguments for the “gaming” prong isn’t even definitional, it’s based on common sense. If “gaming” doesn’t include sports events, then what does it include? Are we really supposed to believe that, in the wake of the biggest economic crisis in recent history, Congress was worried about someone developing futures contracts involving the World Series of Poker (as referenced by the D.C. District Court opinion (PDF))? And if that truly was the concern, where’s the legislative history that supports this view?

The record may be thin, but what we do have are three examples: The Super Bowl, the Kentucky Derby and The Masters golf tournament–all centered on sporting events. None of them involve non-sporting events.

Taking the second path involves an honest and common-sense interpretation of the statute, which points to a simple conclusion: Sports event contracts are contrary to public interest because the economic purpose test still matters. As far as the Special Rule is concerned, gaming means gambling (PDF).

Rob Schwartz, yes, him again, was in the room when Kalshi agreed with the CFTC on what “gaming” includes. His opening argument:

To build and maintain a thriving derivatives industry that is distinct from the gambling business has been the work of 175 years, and it’s important.

That point is underappreciated. It’s not just the colloquy that needs to be discredited for sports event contracts to survive, it’s Congress’s century-long intent.

Why the CFTC believes it lacks authority over all contingent event contracts, especially against that backdrop, is something of a mystery. Maybe they (the departed Commissioners) saw the writing on the wall: Deregulation was likely en route to futures markets and the fight may have seemed too uphill, too steep to climb.

But in a post-Loper Bright (PDF) world, what the CFTC believes may not matter much. The Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit was already leaning toward the resurrection of the economic purpose as the most plausible reading of congressional intent. The Supreme Court likely will too.

You might say: Okay, maybe Kalshi loses–so what. That might upend the sports event contract business. And, if we push a little further, maybe it even destabilizes the prediction markets business, because without sports, they can’t survive. But state-regulated sports gambling will carry on. We’d simply revert back to the 2024 status quo.

We hear that, but that’s not what we have in mind. When we say the potential upending of the sports gambling industry, we mean exactly that.

This Is How It Unravels

Barron’s published an article (paywall) last week titled Sports Event Contracts Are Replacing Bets. Trump’s Regulator Is Standing Aside. It distilled the debate into two questions:

This playoff turns on two questions within the compass of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the federal agency tasked with prediction markets. Are listed sports contracts, like the Broncos proposition, a kind of swap used to hedge events of financial, commercial or economic consequence? And do they involve “gaming” that’s against the public interest?

This framing is close to what we laid out earlier in this post. Quick clarification on the first question: Exclusive jurisdiction can be established even if sports contracts aren’t swaps. Sports being a commodity is an alternative path to the same outcome. Obviously, if they are swaps, the result is the same.

The second question is spot on. If these contracts involve gaming–either because “gaming” includes sports games (as Kalshi once suggested) or because it simply means gambling (a reading Kalshi itself found plausible)—then the contracts are contrary to public interest. Kalshi dodged that nightmare scenario (for them) by pointing out the CFTC didn’t make an economic purpose argument, and then, by being bailed out when the CFTC dropped the appeal; but the logic still stands.

All that said, answering the two Barron’s questions in the affirmative simply takes the nation back to the status quo, which is the allowance of sports gambling in roughly 80% of the states. That’s reversion to status quo, not the destabilization of an entire industry. The path to the latter goes through asking a final question that Barron’s (and many others) are not asking, yet.

Can the States Do Anything?

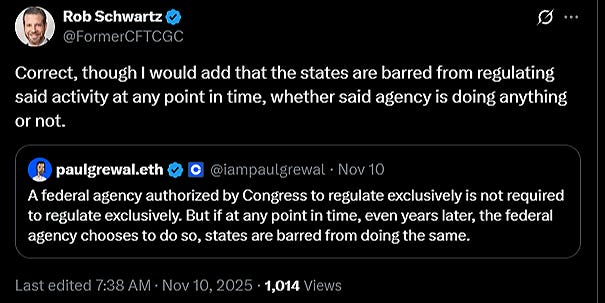

Consider this exchange that is on point, and Rob Schwartz is in the mix again:

Is this Grewal foreshadowing the idea that once prediction markets win on federal preemption, they’ll discard the notion that federal and state regulation can coexist? Coinbase is trying to be a jack of all trades, after all–and they’ve invested in Kalshi and Polymarket.

This is not a fringe view by the way. Quintenz made the exact same argument:

Got that? All events are commodities, which means all contracts on future events are commodity futures contracts, which means all future event contracts need to be traded on a regulated and registered futures exchange. But if the Commission deems any event contract that involves one of the enumerated activities to be contrary to the public interest, that contract is banned from trading on any registered futures exchange. The contract cannot trade anywhere else either since it is still a commodity futures contract and, if traded off of an exchange would be illegal.

We are in agreement as well. Permissible event contracts must trade on a registered futures exchange. State-regulated entities don’t work. If the event contracts are not permissible, well, state-regulated entities still don’t work. Either way, there is no room for state-regulated sports gambling.

You can imagine where Coinbase is headed. We certainly don’t think any prediction market will care about state-regulated sports gambling. That regime was a gap in legal thinking that never should have happened in the first place (which is exactly what Rob Schwartz is saying). But it did happen, and it served its purpose: Getting enough people over the hump to chase the real prize: Nationalized sports gambling.

Wallach and others are clinging to the idea that states should regulate sports gambling. Maybe they think that even if federal preemption takes hold, states will have a role. Perhaps they are encouraged by Kalshi’s current litigation stance that seems to indicate they can co-exist with the states and tribes. We aren’t so sure about that because, based on their patterns, we believe Kalshi could just as easily change course again.

Kalshi conceded to the impermissibility of sports event contracts when it needed to prevail on election contracts, and then did a full 180. If they win on federal preemption, they’ll just as likely discard the notion that state-regulated sports gambling can coexist with federal oversight. Why wouldn’t they? Fewer competitors. They’ll also have a solid legal argument.

Putting It All Together

Kalshi’s survival depends on the answers to three legal questions:

Question 1 - Is sports a commodity/are sport event contracts swaps (federal jurisdiction)

Question 2 - Are sports event contracts permissible? (gaming/economic purpose)

Question 3 - Can there be an overlap between federal and state powers? (off-exchange futures trading)

Kalshi is making a decent effort to isolate the questions and adjusting its strategy on the fly. That is their legal strategy—moving the ball incrementally.

They answered #2 with a no to kick off the election market business, then did a 180, to shoot for the real prize: Sports. Now, under pressure, they answer #1 with a yes, but simultaneously #3 with a yes as well.2 They are not bothered by states, and state-licensed operators dipping in for a little longer; it’s better to be perceived as extending an olive branch: let’s eat together. Once they’re too big to fail they will likely change their answer on #3 to a no and drive state-licensed operators out of business.3

If that happens, Kalshi will have provided the correct legal answer to each of these questions (yes/no/no) at some point, in some litigation. It is critical for them not to face these questions at the same time.

That’s the real win for Kalshi (and other similarly situated prediction markets). They may lose some battles, to the rejoice of proponents of state regulation, but they seem to be winning the war. The judiciary evaluating these questions in an isolated matter itself is a win for prediction markets. The gaming/economic purpose question was brushed aside early on, their Achilles’ heel. They have much stronger arguments on #1 and #3. But the courts are not really pushing them on #3 at this time, and they prefer it that way. They can fight #1 (preemption), and wait out on #3.

It is heartbreaking to see how all of this is unfolding, and there really is only one way to fix all this. An APA challenge going all the way to the Supreme Court, where these three questions can be looked at holistically.

A quick preview of how the answers change drastically when the questions are looked in the following baskets:

#1 and #2 together

It’s fascinating to consider that if you add the two opposing arguments Kalshi made in litigation within the last year, you can envision their demise.

#1 and #3 together

If the gaming/economic purpose question is tossed out the window, congratulations; our nation just upended a century-worth of congressional intent. In this scenario, prediction markets and state-licensed operators coexist, until one of the prediction markets decides to argue there can be no off-exchange futures trading.

#1, #2 and #3 together

It’s even more thrilling to consider that if you add Grewal’s argument to the mix–or side with Quintenz’s framing, you can wind up with a much more dramatic outcome:

All the dominos fall. The entire sports gambling industry goes down with Kalshi.

More precisely, litigation started in late 2023 and carried into early 2025 (including the appeals process).

During oral argument in Third Circuit, Kalshi took the position: “”Nothing .. limits states from subjecting sports books to their own state authority.”

Perhaps one early signal that they may eventually sharpen their pencils on is the position they took in Maryland in their supplemental brief: “Section 40.11 shows that the CFTC understands itself to possess jurisdiction over these contracts, meaning states lack jurisdiction… Even if sports-event contracts ran afoul of a CFTC regulation, they would still be swaps covered by the exclusive-jurisdiction provision, and Defendants would still lack a basis to regulate them.” In this particular instance, they likely meant ‘on DCMs.’ But it won’t be that difficult to lose the phrase ‘on DCMs’ in future litigation.

If you had to assign odds...how would you estimate them across outcomes? Very interesting read!